When the negotiators in the Uruguay Round of the GATT introduced the concept of the ‘green box’ – farm support measures that are minimally or non-trade distorting and therefore exempt from any limits – few would have foreseen that within 15 years, the bulk of farm support in the developed world would be in the green box. A new book “Agricultural Subsidies in the WTO Green Box: Ensuring Coherence with Sustainable Development Goals”, published by Cambridge University Press, shows the extent to which farm support has been shifted out of more traditional, trade distorting measures and into the green box. It addresses the vexed question of whether green box supports are really as trade-neutral and environmentally beneficial as they are claimed to be.

The book features chapters from many of the leading lights of in agriculture and trade economics including David Orden, Alan Swinbank, Tim Josling, Harry de Gorter, David Blandford. NGOs analysis are also among the contributors including Ariel Brunner of BirdLife International, an occasional contributor to this blog, Teresa Cavero of Oxfam-Intermon and Carlos Galperín of the Argentinian think tank Centro de Economía Internacional. There are also chapters by Pedro de Camargo Neto, a former trade negotiator for Brazil, and Ann Tutwiler, who was appointed to the Obama Administration in the US earlier in the year with special responsibility for trade and development in Africa. It’s an impressive cast list. One of the book’s contributors, Vincent Chatellier, explains out the kind of subsidies that can qualify for the green box:

Within the green box, there are two types of subsidy. The first relates to public service programmes. This consists mainly of general services such as research, training, dissemination, and inspection (health, safety, quality control and normalisation), sales, promotion and infrastructural services. Domestic food aid or the stockpiling of foodstuffs for purposes of food security also falls into this category. The second concerns direct payments to producers. Article 6, Annex 2 of the URAA (box 1) sets out the conditions that govern the allocation of decoupled income support to the green box. It specifies that these subsidies should not be linked to either production, or factors of production (land and livestock), nor even to an objective price. This applies mainly to income guarantee and security measures (natural disasters, State contribution to crop insurance, etc.) ; to structural adjustment measures (farmers’ retirement schemes, withdrawal of land from production, investment grants) ; and environmental protection programmes.

According to countries’ latest official reports to the WTO, the US provided $76 billion in green box payments in 2007 – over nine-tenths of its total spending – while the EU notified €48 billion ($91 billion) in 2005 , or around half of all support provided by the bloc. The book is the first ever attempt to look at green box support from a ’sustainable development’ viewpoint, examining how payments affect economic, social and environmental progress in both the developed and developing world.

The EU’s embrace of the green box is the legacy of Franz Fischler, whose major reform of the CAP was agreed in 2003 and from 2005 shifted the bulk of taxpayer support for farmers into the green box by maintaining exactly the same distribution of farm subsidy payments as previously but decoupled from current production levels. The G20 grouping of agriculture-oriented developing countries has been quick to argue that, green box or not, the EU’s new decoupled supports could not be non-distorting, as the sheer scale of the payments would insulate farmers against fluctuations in price, provide additional finance for investment. They repeated their refrain, ‘Developing world farmers can compete with farmers in the EU and the US, but we can’t compete with their finance ministries.’

I have always understood that the green colour of the green box comes from the Green means Go of a traffic light (as opposed to the red and amber boxes that are subject to strict limits). But for some, and particularly those politicians who advocate these payments, the hue of the green box owes something to its environmental credentials. In a thorough analysis of the EU situation, Ariel Brunner and Harry Huyton show this argument to be false. They argue that “abuse of the green box is damaging the reputation of agricultural support, which can deliver genuine social and environmental benefits” and that while the current green box rules allow for abuse they mitigate against the kind of environmental support measures that are needed to reverse biodiversity decline.

Brunner and Huyton argue that the single payment scheme, which accounts for the bulk of the CAP’s direct payments to farmers, is not about maintaining environmental, food safety, animal and plant health, and animal welfare standards but about improving farmer incomes. They give a startling example. On the RSPB’s 181-ha arable farm in Cambridgeshire, England it was calculated that the costs of implementing cross-compliance were approximately €75 compared to €27,000 received in direct payments.

Meanwhile, WTO rules on what qualifies for the green box rules out certain agri-environment programmes that seek to pay farmers to enter ‘contracts’ in which they agree to meet specific standards of environmentally-friendly land management. Steenblik and Tsai make a similar point in their chapter on the environment and the green box. This observation leads Brunner and Huyton to argue for a change to the green box rules that would have a profound impact on the measures that are currently designated as green box:

A second fundamental requirement should be introduced, in addition to the current requirement that green box support has no, or at most minimal, trade-distorting effects on production. This should require green box support to be targeted specifically at delivering environmental and social benefits, i.e. “public” benefits that are not already delivered by the market.

This would, at a stroke, disqualify measures that are primarily ‘income support’ policies from the green box and bring the WTO rules into service of BirdLife’s notion of ‘public money for public goods’.

Elsewhere in the book, Carlos Galperín and Ivana Doporto Miguez address the question of whether there is a cumulative effect of green box subsidies when it comes to distorting trade. Taking the reader step-by-step through the micro-economics of farm level production decisions in response to different kinds of subsidies, they show that decoupled support does not impact on short term production decisions, but it does impact on long term decisions about whether to stay in farming or not, and thus favours those farmers in countries with generous income support policies, making life harder for farmers in the developing world where governments are not rich enough to pay similar aids.

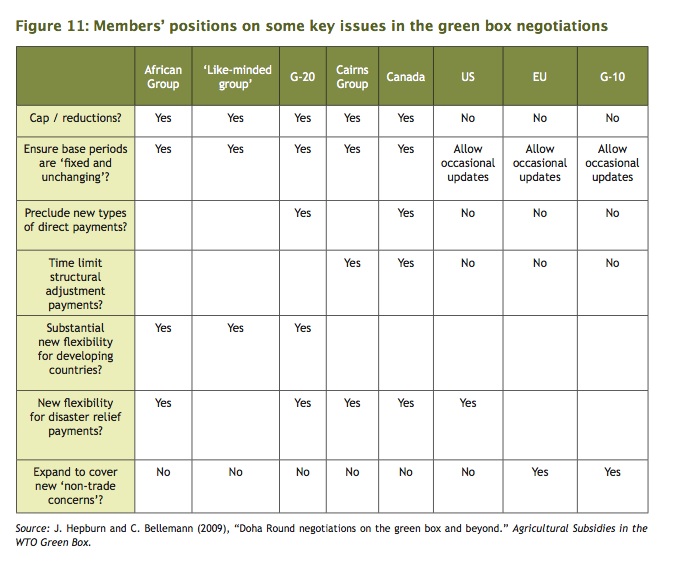

Galperín and Doporto Miguez discuss solutions capping green box payments, limiting the overal size of the green box and limiting green box payments to producers not in receipt of support that is designated in any of the other boxes. The fact that they don’t come down in favour of any particular solution to the problem of accumulation of green box supports and the impact on production decisions reveals how far we are from reaching an agreement at the WTO on the subject. The authors concede this is likely to be a subject for negotiations after conclusion, or abandonment, of the current Doha Round. The editors of the book provide a handy table showing the negotiating positions of the various actors at the WTO on key green box issues (see below).

There is plenty more in this book to digest and debate, far more than can be covered in a single blog post but it is clear that the current and future status of the WTO green box is incredibly significant – both for patterns of international trade and for agriculture and environment policies. The book can be ordered here and for those that can’t afford the £80 price tag or want a shorter read there is a 16 page breifing note from International Centre for Trade and Sustainable Development, the NGO that provided the impetus for the book.