Environmental NGOs were harsh in their immediate criticism of the legislative proposals on the new CAP. Greepeace said that the EU farming plan “could spell disaster for the environment”. BirdLife Europe said that “The European Commission’s claim that the new proposal will deliver a higher environmental and climate ambition has fallen flat”, arguing that the new plan “does not guarantee any spending on biodiversity and grotesquely slashes funds ring-fenced for the environment across the board”.

Birdlife Europe has produced a detailed assessment of the Commission’s proposals in a handy tabular form, pointing out both weaknesses in the proposals themselves as well as omissions where the proposals could be strengtened (a summary of this assessment has appeared on this blog).

In this post, I review some of the issues raised by these critiques and explain some of the key differences between the proposed new greening architecture and the policy that it would replace. The leitmotiv of the legislative proposal as a whole is to devolve responsibility to Member States to design their menu of interventions funded by the CAP in the form of a Strategic Plan in line with a needs assessment.

The key take home message is that this flexibility could allow the ambition that is necessary to move agricultural production in a more sustainable direction in the way the environmental NGOs would desire. But at the same time it puts limited constraints on Member States for whom this goal is not seen as a priority, leaving open the risk that these opportunities will not be used. We return at the end to discuss some ways in which this gap might be filled.

Visualising the new greening architecture

I reproduce below the slide the Commission has used to explain the new greening architecture. There are three components. A new ‘enhanced conditionality’ replaces the current cross-compliance and greening payment requirements. A new eco-scheme is proposed in Pillar 1. And voluntary agri-environment-climate measures (AECMs) would continue in Pillar 2.

In itself, this slide tells a story, because it suggests two alternative architectures. One is where Member States use some of their Pillar 1 money to fund the eco-scheme, and then offer a more demanding menu of options to farmers who are prepared to opt into a more ambitious AECM. In the other option (right hand side), the Member State does not offer the eco-scheme and relies solely on voluntary enrollment in an AECM for management practices that go beyond enhanced conditionality.

This slide was being used in Commission presentations to the Council as late as March this year and possibly even later. However, in the legislative proposals, this right-hand option has been eliminated. The proposals make clear that Member States shall introduce an eco-scheme (even if the amount of funding allocated is left open, see below), so the option of not doing so has been removed.

Whether this was the result of the inter-service consultations and pressure from DG Environment within the Commission or for other reasons will be up to the historians to uncover. Nonetheless, it illustrates that key elements of the Commission proposals were still in play until shortly before their announcement on 1 June. As another example, the hierarchical relationship suggested in the diagram between the eco-scheme and voluntary AECMS in which the latter require more demanding measures is not necessarily reflected in the legislative proposals which leave open that either scheme could fund broadly similar measures, although the commitments funded under AECMs must be different than those funded under the eco-scheme (this is further discussed below).

A higher level of ambition

The starting point for the new greening architecture is the commitment that a modernised Common Agricultural Policy must enhance its European added value by reflecting a higher level of environmental and climate ambition. The Commission points out that, in the November 2017 CAP Communication, it “identified higher environmental and climate action ambition, the better targeting of support and the stronger reliance on the virtuous Research-Innovation-Advice nexus as top priorities of the post-2020 CAP.”

Or as the preamble to the draft CAP Strategic Plan Regulation makes clear: “Bolstering environmental care and climate action and contributing to the achievement of Union environmental- and climate-related objectives is a very high priority in the future of Union agriculture and forestry. The architecture of the CAP should therefore reflect greater ambition with respect to these objectives”.

So this is the standard by which the proposals should be judged.

Articles 5 and 6 of the draft Strategic Plan Regulation identify three general objectives for the CAP. One of these is to bolster environmental care and climate action and to contribute to the environmental- and climate-related objectives of the Union. In turn, this is broken down into three specific objectives:

• Contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as sustainable energy;

• Foster sustainable development and efficient management of natural resources such as water, soil and air;

• Contribute to the protection of biodiversity, enhance ecosystem services and preserve habitats and landscapes.

Let us now see how the new green architecture proposes to deliver a higher ambition with respect to these objectives.

Enhanced conditionality

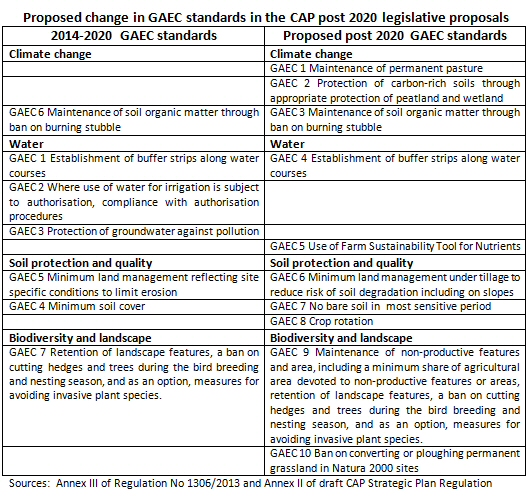

The nature of the enhanced conditionality proposed by the Commission for the CAP post 2020 is shown in the table below. There are two sets of changes. One is to (re-)incorporate the three greening practices into the conditionality, as GAEC 1 permanent pasture, GAEC 8 crop rotation (to replace crop diversification) and GAEC 9 non-productive areas (to replace Ecological Focus Areas).

It is important to underline that, in making this change, all of the exemptions which limit the scope of the greening practices in the current CAP (e.g. organic farms, farms below a certain size or below a certain arable area) have been eliminated. In future, these requirements would apply to all farms in receipt of direct payments, unless Member States are able to reintroduce them in their Strategic Plans – this is not clear.

The other change is the addition of new requirements GAEC 2 to protect carbon-rich soils, GAEC 5 to make compulsory the use of the new Farm Sustainability Tool for Nutrients and GAEC 10 the ban on converting grassland in Natura 2000 sites. GAEC 5 means that the need to have a nutrient management plan is extended to all agricultural land, and not only land in Nitrates Vulnerable Zones as currently.

Furthermore, the number of SMRs has been increased with the addition of requirements to respect oblgiations under Water Framework Directive and the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Directive (as well as a further regulation on transmissable animal diseases though this is outside the scope of environmental issues).

(click on figure for a clearer image)

Member States will be required to define, at national or regional level, minimum standards for beneficiaries in line with the main objective of these GAEC standards, taking into account the specific characteristics of the areas concerned, including soil and climatic condition, existing farming systems, land use, crop rotation, farming practices, and farm structures.

Member States will also be able to prescribe standards additional to those laid down in the Annex to the proposed Regulation against those main objectives. However, to protect against gold-plating, Member States are not allowed to define minimum standards for main objectives other than the main objectives laid down in the Regulation. This does not prevent Member States from requiring farmers to observe additional standards. It only means that the cross-compliance mechanism, whereby a farmer’s direct payments are reduced in the case of infringements, cannot be applied to ensure enforcement in those situations.

The new GAECs are welcome and underpin the enhanced conditionality sought by the Commission. The criticism is made that Member States may interpret them in a lax way, as previous evaluations of cross-compliance in practice have found. For example, Ecological Focus Areas are required to be a minimum of 5% of the arable area on those farms to which it applies in the current CAP but there is no minimum area specified for non-productive areas in GAEC 9. Some Member States might be tempted to set the standard at 1% of the arable area while others might opt for 3% or even 5%.

As we will see throughout this blog post, the proposed Regulation gives Member States lots of tools to be environmentally ambitious if they choose, but there are limited formal constraints in the legislation to require them to be so. Ultimately, it will all come down to the quality of the programming process at both Member State and Commission level.

Eco-scheme

The second innovation in the green architecture is the requirement that Member States must implement an eco-scheme financed from their Pillar 1 direct payments ceiling (Article 28 of the draft Strategic Plan Regulation). These are defined as voluntary schemes (for farmers) for the climate and environment and should be specified in greater detail in their Strategic Plans. As the draft Regulation proposes that Member States will also be obliged to offer AECMs to farmers under Article 65, the question might be asked what is the point of have two instruments focused on the one set of objectives.

It is important to point out two differences between the compulsory eco-scheme under Article 28 and the compulsory AECMs under Article 65.

One difference concerns what can be compensated. AECMs follow the traditional limitation that beneficiaries can only be compensated for costs incurred and income foregone resulting from the commitments made. This is the language taken from the requirements for Green Box measures when notifying agricultural support to the WTO. Where necessary, they may also cover transaction costs. Member States may grant support as a flat-rate or as a one- off payment per unit.

Support for eco-schemes must take the form of an annual payment per eligible hectare. Importantly, it shall be granted either as

• (a) a payment additional to the basic income support; or

• (b) as a payment compensating beneficiaries for all or part of the additional costs incurred and income foregone as a result of the commitments as set pursuant to Article 65.

Option (a) does away with any necessary link between the payment received by a farmer and the costs (or value) of achieving an environmental outcome. It allows the possibility of a much larger element of income support in an environmental payment than would be permitted under an AECM designed to be consistent with WTO rules.

Option (b) is not a model of drafting and it is difficult to interpret what is implied by the reference to “commitments as set pursuant to Article 65”. One admittedly far-out interpretation is that, for a beneficiary who enrols in a voluntary AECM under Article 65, the Member State could use the eco-scheme funding in Pillar 1 to partially or fully fund the payment to compensate him or her without having to formally transfer the funds to EAFRD. This would be a budgetary nightmare and surely not what the drafter intended.

A more plausible interpretation might be that the eco-scheme can be used to fund management practices beneficial for the environment and climate on the same basis as in Article 65 (that is, they go beyond the SMRs and GAEC standards in the enhanced conditionality and the conditions established for the maintenance of agricultural areas). However, in this case, why the eco-scheme would only pay part of the additional costs involved is not obvious (as this is a voluntary scheme for farmers, this would be a sure way to guarantee zero enrollment). Nor is it obvious why an option (b) is necessary and why payments would not be covered anyway under option (a) (though see below for a possible answer to this question).

Only limited guidance is given as to what might be funded by Member States with the eco-scheme. In the preamble to the draft Strategic Plan Regulation, there is an indication that “Member States may decide to set up eco-schemes for agricultural practices such as the enhanced management of permanent pastures and landscape features, and organic farming. These schemes may also include ‘entry-level schemes’ which may be a condition for taking up more ambitious rural development commitments”. However, the legislation states that the eco-scheme can be designed to meet any of the environmental-climate specific objectives outlined above, just as AECMs funded from Pillar 2.

In one of the options (3a) in the Impact Assessment, the Commission models a range of practices funded by the eco-scheme. These include winter soil cover; permanent crop crop between trees or permanent crop area; a three year crop rotation; 5% non-productive arable land; reduction targets of nutrient surplus; a strong push on the development of Integrated Pest Management; a reduction of antibiotic use; the development of cattle genomics targeting GHG efficiency.

Leaving aside the need to work around what seem to be potential overlaps with some of the GAEC standards in enhanced conditionality, this list illustrates the very wide scope that eco-schemes could potentially embrace.

The second difference between eco-schemes and AECMs relates to who can benefit. Member States are required to limit support under eco-schemes to genuine farmers, or at least to those benefiting from support under possibility (a) in the previous discussion. Support under AECMs, on the other hand, can be paid to “farmers and other beneficiaries” who undertake, on a voluntary basis, management commitments which are considered to be beneficial to achieving the specific objectives set out in Article 6. Thus, environmental trusts that manage land can be supported under AECM Pillar 2 funding.

While environmental trusts cannot be funded under option (a) for funding the eco-scheme, it may be that they can be funded under option (b). This is because option (b) allows for compensating “beneficiaries” (not only genuine farmers) on a costs foregone basis “as a result of the commitments as set pursuant to Article 65”. Here the reference to Article 65 could be interpreted as allowing a broader range of beneficiaries, provided they are not allowed to benefit from the income support hidden in option (a).

It all sounds terribly complicated and seems to arise from a desire to have an eco-scheme that can both be an income support scheme for so-called ‘genuine farmers’ but might also fund ‘proper’ agri-environment-climate schemes for non-farmer beneficiaries such as environmental trusts.

Voluntary AECMs

The third change in the new green architecture is that the various agri-environment-climate interventions available under the current Rural Development Regulation are collapsed into a single Article 65 which refers to environmental, climate and other management commitments. Eco-schemes can only fund farmers for practices which target the three specific environment and climate objectives out of the nine specific objectives specified for the CAP in Article 6 of the draft Strategic Plan Regulation. Article 65 is considerably broader than the corresponding Articles in the current Rural Development Regulation. It refers to support for environmental, climate and other management commitments, provided they target any one of the nine specific objectives set out in Article 6.

One issue here is the relationship between a country’s AECM and its eco-scheme. Under Article 65, Member States can only fund management commitments in an AECM that are different than those funded in the voluntary (for farmers) eco-scheme. Thus, a farmer who wanted to enrol in both will have to make two separate applications. The option is also there that countries may require a farmer to enrol in the eco-scheme as a condition for enrolling in the AECM.

Getting these two schemes to work together in a way that makes sense from an the point of view of maximising environment and climate objectives is going to be a challenge for Member States.

Some concern has been expressed that this might open the door to using Pillar 2 money under this Article for measures mainly targeting economic viability or territorial cohesion rather than agri-environment-climate. However, only agri-environment-climate schemes under this Article are mandatory. The preamble to the Regulation gives the following examples of what might be funded under this Article, even though the legal text in Article 65 seems much broader:

Member States should grant payments to farmers and other land managers who undertake, on a voluntary basis, management commitments that contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation and to the protection and improvement of the environment including water quality and quantity, air quality, soil, biodiversity and ecosystem services including voluntary commitments in Natura 2000 and support for genetic diversity. Support under payments for management commitments may also be granted in the form of locally-led, integrated or cooperative approaches and result-based interventions. Support for management commitments may include organic farming premia for the maintenance of and the conversion to organic land; payments for other types of interventions supporting environmentally friendly production systems such as agroecology, conservation agriculture and integrated production; forest environmental and climate services and forest conservation; premia for forests and establishment of agroforestry systems; animal welfare; conservation, sustainable use and development of genetic resources. Member States may develop other schemes under this type of interventions on the basis of their needs.

Farm advisory service

An important part of the new green architecture is a beefed-up farm advisory service for the purpose of improving the sustainable management and overall performance of agricultural holdings and rural businesses, covering economic, environmental and social dimensions. These farm advisory services should help farmers and other beneficiaries of CAP support to become more aware of the relationship between farm management and land management on the one hand, and the standards and requirements, including environmental and climate ones, they are asked to follow on the other hand. This emphasis on knowledge transfer and engaging farmers more around the practices they are asked to follow can only be welcomed.

Funding for the new green architecture

Another concern that has been expressed is that the funding will not be there to implement the higher level of environmental and climate ambition even where the Regulation facilitates it. This concern is even more forcefully expressed in the light of the proposed reduction in the budget for Pillar 2 payments (for the figures, see this post). Farm unions push back against being asked to do more for less money. The environmental NGOs worry about the apparent lack of ring-fencing in the CAP budget for agr-environment-climate objectives.

Bolstering Pillar 2 funding. In principle, there is scope to make up for the reduction in the Pillar 2 CAP allocations to Member States in five ways:

• Member States can be asked to increase their national co-financing of Pillar 2 expenditure. This option is already included in the draft Strategic Plan Regulation where, in line with other European Structural and Investment Funds, the national co-financing rates have been increased by 10 percentage points.

• Member States can top up their Pillar 2 spending out of their own resources without falling foul of State aid rules.

• Member States can make use of the flexibility to shift resources between their Pillars. There is a general allowance for Member States to shift up to 15% of either Pillar in either direction. This symmetry conceals the fact that 15% of Pillar 1 funds will generally be much greater in absolute terms than 15% of Pillar 2 funds. In the current CAP period, there was a net transfer from Pillar 1 to Pillar 2. Money transferred in this way does not require national co-financing (Article 85(3)).

• Member States may, in addition, transfer up to a further 15% of their Pillar 1 allocation to Pillar 2 provided it is used for interventions addressing environmental and climate objectives. The percentage amounts under this and the previous bullet point can vary from year by year but must be specified in advance in the CAP Strategic Plan, though Member States can review these decisions as part of a request for amendment of the Plan.

• Finally, for the sake of completeness but nothing else, we should mention that money from the proceeds of capping can be transferred to that Member State’s Pillar 2 allocation on top of these other transfers. However, as the yield from capping as proposed is expected to be very limited in most Member States, in practical terms this is irrelevant.

Birdlife Europe has argued that, in order to allow a higher level of environmental and climate ambition, a Member State should not be constrained at all in the percentage share of its Pillar 1 ceiling that it can transfer to AECMs in Pillar2. However, the relative sizes of the two Pillars is now much less important, given that Member States, if they wish, can spend their Pillar 1 ceiling directly on agri-environment-climate measures through the eco-scheme.

In the Impact Assessment, under the Option 3 scenario which is the one most emphasising environmental and climate ambition, the Commission simulated the impacts of between 30% and 60% of a Member State’s Pillar 1 ceiling allocated to the eco-scheme, with the share of the basic income payment falling to just 25% of the ceiling in the latter case. Once again, it is more the political will of Member States to make use of these possibilities rather than the Regulation itself which is at issue.

Minimum spending thresholds. There are three minimum spending commitments which attempt to maintain a high level of environmental and climate ambition: a climate expenditure tracker; a minimum spend on AECMs; and a no back-sliding commitment. Let us examine each of these in turn.

Minimum CAP spend on climate action. Actions under the CAP are expected to contribute 40% of the overall financial envelope of the CAP to climate objectives (Recital 52 of the draft CAP SP Regulation). To allocate particular categories of development co-operation expenditure to climate in its development assistance effort, the EU uses the system of ‘Rio markers’ when reporting on its expenditure on climate and environmental aid commitments to the OECD. It has now taken over this system to track climate expenditure in the EU budget as a whole.

The ‘Rio markers’ (see this explanation here) distinguish between expenditure that is (a) principally targeted (b) significantly targeted or (c) not targeted at climate objectives. Depending on the degree of targeting, fixed percentages of the overall budget are considered to be relevant for the theme. The EU uses 0%, 40% and 100%, respectively for non-targeted, significantly-targeted and principally-targeted expenditure.

On this basis, Article 87 of the draft Strategic Plan Regulation assigns the following weights to different CAP instruments when tracking climate expenditure:

• 40% for the expenditure under the Basic Income Support for Sustainability and the Complementary Redistributive Income Support

• 100% for expenditure under eco-schemes

• 100% for expenditure for the interventions that count towards the minimum 30% for AECMs (see next section)

• 40% for expenditure for natural or other area-specific constraints.

One can debate whether these assignments are more than a book-keeping exercise and actually reflect real mitigation and adaptation action on the ground. On the other hand, expenditure on some measures, including knowledge transfer and some investments, do not get covered in this tracker. Whether real or not, the climate tracker 40% minimum limit could prove to be a constraint for a Member State that wanted to prioritise spending on coupled support (in Pillar 1) and investment aids (in Pillar 2).

Minimum 30% spend on AECMs. This obligation is contained in Article 86 of the draft Strategic Plan Regulation. At least 30% of the total EAFRD contribution to the CAP Strategic Plan shall be reserved for interventions addressing specific environmental and climate-related objectives in AECMs. Recall that AECMs are mandatory, and unlike the eco-scheme this provision requires a minimum 30% spend of the Pillar 2 ceiling on these schemes.

One important change compared to the current period is that expenditure on Areas of Natural Constraints and areas with other specific constraints is no longer included in this envelope. Even with a smaller EAFRD budget, this will require increased spending on AECMs in some countries that did not prioritise this objective in their current Rural Development Plans.

No backsliding. Both of the previous commitments are expressed in percentage terms. With a smaller EAFRD budget, spending in absolute terms could still decrease. This is where Article 92 which is meant to copper-fasten the Commission’s commitment to increased ambition with regard to environmental- and climate-related objectives becomes important.

Article 92 requires that Member States “shall aim” to make a greater overall contribution to achieving the specific agri-environment and climate objectives in their CAP Strategic Plans as compared to the contribution to the sustainable management of natural resources and climate action through support under the EAGF and the EAFRD in the current programming period. In an earlier version of this post, I had argued that this implied a comparison of financial commitments to address environmental and climate issues in the two programming periods, but this is not the case.

Instead, Member States are asked to explain in their CAP Strategic Plans how they intend to achieve the greater overall contribution based on “relevant information” drawn mainly from the needs assessment, SWOT analysis, intervention logic, targets and financial plans included in the Strategic Plan. In a subsequent post, I argue that this is rather a toothless commitment because it evaluates a Member State’s intentions rather than outcomes and requires a qualitative rather than quantitative assessment and is thus much easier to fudge. This Article badly needs to be strengthened if it is to contribute meaningfully to delivering on increased environmental and climate ambition.

Performance bonus. A final innovative element introduced in the draft Strategic Plan Regulation is the notion of a performance bonus that would be attributed to Member States in the year 2026 to reward satisfactory performance in relation to the environmental and climate targets.

In 2026, the Commission will withhold an amount equal to 5% of each country’s allocation for the 2017 financial year. This will be released (attributed) to the Member State provided that its performance review in 2016 shows that the result indicators applied to the specific environmental- and climate-related objectives in its CAP Strategic Plan have achieved at least 90% of their target value for the year 2025.

There are some technical points left unclear in this formulation. There are 18 result indicators for these specific objectives labelled R12 through R29. Does a Member State have to reach at least 90% fulfilment on all of these result indicators or just an arithmetic average? What happens in the case of a country like Belgium which will have one CAP Strategic Plan but say Wallonia meets the 90% criterion but Flanders does not and, as a result, the country as a whole falls short of the target?

My greater concern is that this performance reserve will act as a perverse incentive. To avoid the risk of not hitting the 90% target, the obvious incentive for a Member State is to set the target as low as possible. In its Plan the Member State is going to have to show how it intends to draw down the CAP money, so reducing targets in one area (which are usually set as a share of the farm population participating in a scheme, or the share of the UAA covered by a scheme) will require targets to be increased in another area. If only agri-environment-climate performance is penalised in this way, then Member States have an extra incentive to shift funds from this ‘risky’ set of activities to ones where the performance reserve will not apply.

Conclusions

This reading of the new green architecture put forward in the Commission’s legislative proposals suggests a more optimistic picture than the initial reactions of the environmental NGOs. What I emphasise here is the potential, or the possibility, for Member States that wish to focus more on raising the level of environmental and climate ambition to do so. The enhanced conditionality can potentially be a significant advance on the combined cross-compliance and greening rules. With respect to expenditure, the Article 92 clause (assuming it survives the legislative process) seems to guarantee that at least spending on agri-climate-environmental measures will not fall in the post-CAP 2020 period.

In view of the urgent need to address the environmental and sustainability challenges of agricultural production in Europe, this will seem to many as a very low bar. And indeed, we must try to do better. And here there are two possible paths.

One way to go is to try to write greater ambition into the basic regulation itself (e.g. higher minimum thresholds for AECMs, minimum percentages for non-productive areas in GAEC). Such an approach will be popular among activitists in those countries (including my own, Ireland) where historically there has been a limited appetite for ambitious environmental and climate interventions and where, as a result, much environmental improvement has depended on prodding and compliance with EU legislation.

It could also be popular, paradoxically, with farm unions in high-ambition countries who worry that too big a gap between the level of standards they face and the alleged risk of lower standards in low-ambition countries could hurt their competitiveness. Exporting higher standards through EU legislation is then a way of levelling the playing field to their advantage.

On the other hand, this approach goes against the philosophy of returning greater responsibility to Member States in the New Delivery Model. It also risks going against the political tide which sees ‘Europe’ imposing rules and regulations against the wishes of national parliaments and populations.

The Commission’s response is to point to the checks and balances built into the formulation and approval of the CAP Strategic Plans: the requirement to have a wide group of stakeholders involved in drawing up the Plans; the requirement to justify the choices made among competing specific objectives by reference to objective indicators and a needs assessment; the requirement to justify the choice of interventions and the definition of GAEC standards to meet these objectives through a clear intervention logic; the requirement for Commission approval of the Plans in the light of data and methodology used; and the requirement to meet the (minimal) requirements set out in the basic legislation.

It’s a defence that deserves to be taken seriously. Whether it works or not with respect to the goal of achieving a higher level of environmental and climate ambition which is the stated objective of the proposal will largely depend on the openness of the processes used to formulate the Strategic Plans; the calibre of the officials involved in drawing up the Plans and their ability to think strategically; the rigor of the approval process by the Commission; and in particular on the ability of transparency (around the objectives identified, the instruments chosen and the associated indicators) to break at the national level the political log-jam around agricultural policy-making at the Brussels level. For many Member States, this will be a tall order.

These are the areas where attention will need to be focused if the proposed legislation is approved.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Photo credit: Somerset Levels, UK Wikipedia under CC licence

Update 20 June 2018: This post was corrected to make clear that funds transferred from Pillar 1 to Pillar 2 under flexibility and capping provisions do not require national co-financing as part of EAFRD. Also the relationship between the eco-schemes and AECMs was further elaborated.

Update 30 June: The inference that Article 92 would require Member States to keep financial commitments to address environmental and climate objectives at least at the level of the curent programming period has been corrected and removed, and the link to a subsequent post explaining this point in greater detail has been added.

Although this article misses various key dangers with the CAP proposals – coupled subsidies for biofuels, the lack of environmental safeguards on investment spending and coupled payments, the removal of safeguards (such as those in the current CAP on irrigation expansion), and unsound methodology for tracking climate spending – it otherwise generally sets out many of the reasons why the environmental NGOs were so skeptical. The experience of previous reforms, and especially the greening, shows that Member States have systematically used flexibility to go for the least ambitious environmental options, as highlighted in the Court of Auditors’ “Special Report n°21/2017: Greening: a more complex income support scheme, not yet environmentally effective”. When there is an environmental crisis in EU farmland due to intensive agriculture, it is not sufficient to leave the environmental delivery to chance and wishful thinking, especially when this is not in line with what EU citizen’s demanded in the Consultation on the CAP, or what was promised in terms of a ‘transition to sustainable farming’ in both the CAP and the EU Budget Communications.