Beef is generally considered to be a sensitive sector in the EU-US negotiations on a possible Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreement. Currently, imports of beef from the US are limited by high tariffs and by the refusal of the EU to allow the import of beef produced with the aid of pharmaceutical technologies such as hormones and beta-agonists (a class of non-hormonal compounds that act to increase feed efficiency).

Nonetheless, EU imports of non-hormone-treated beef from the US have been increasing in recent years. Different views have been expressed about the likely consequences for the EU beef market if market access were further liberalised under a TTIP agreement. I examine the background to this issue in this post.

The WTO beef hormones dispute

Negotiations to increase US access to the EU market for beef as part of a TTIP agreement take place against the background of special trade concessions agreed following a complex series of disputes taken originally under the GATT and, subsequently, under the WTO’s dispute settlement process.

These disputes originated in an EU ban introduced in 1989 on meat and meat product imports from animals treated with six growth promoters, all of which were approved for use in beef production in the US (hormones are not approved for use in poultry and pigmeat production in the US). The US instituted retaliatory tariffs (100% ad valorem) on EU imports valued at $93 million, which remained in effect until May 1996.

In 1996, when the EU voted to maintain the ban, the US initiated a dispute process under the new Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS Agreement) which came into force with the establishment of the WTO in 1995. The WTO found against the EU on the grounds that it had not scientifically proven that the hormones in question posed a cancer risk to consumers.

The EU sought more time to undertake its risk assessment, and in 1999 the US (and Canada) were authorised by the WTO to suspend tariff concessions on imports of EU products up to a value of $117m and $11m, respectively. In 2003, the EU introduced new regulations which permanently banned one of the six growth promoters and provisionally banned the use of the other five while it sought more complete scientific information. With this new legislation replacing its original ban with a provisional ban based on the precautionary principle, the EU deemed it was now in compliance with its WTO obligations.

This argument was not accepted by the US and Canada. They maintained their higher tariffs, and in 2004 the EU initiated a new WTO case seeking the removal of these sanctions. The WTO Appellate Body ruled in 2008 that the US and Canada could continue to impose their trade sanctions but also that the EU could continue to ban imports of hormone-treated beef.

(For further detail on these disputes, see the one-page WTO summary of the original dispute and also the one-page summary of the compliance dispute. A more detailed description of the dispute and its impact on US beef trade with Europe can be found in this Congressional Research Service report. The European Commission DG TRADE has prepared this detailed timeline of the dispute.)

The US-EU Memorandum of Understanding

On 13 May 2009, the EU and the US reached a political agreement to freeze the WTO case through the signature of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) which allowed the import of US beef from animals not treated with growth-promoting hormones in exchange for the removal of the duties applied by the US to certain EU products.

The agreement set out three phases:

- Phase I (August 2009 – August 2012) : lifting of US retaliatory sanctions on some EU agricultural products in exchange for the opening of a zero-duty tariff-rate quota (TRQ) for high quality hormone-free beef (‘High Quality Beef’) (20,000 tonnes). The new quota was in addition to the pre-existing 11,500 tonnes of so-called ‘Hilton beef’ allowed entry into the EU (this is the US/Canada share of a larger quota of high-quality beef opened following the GATT Tokyo Round of multilateral trade negotiations in the 1970s). The new HQB quota is specifically for grain-fed beef.

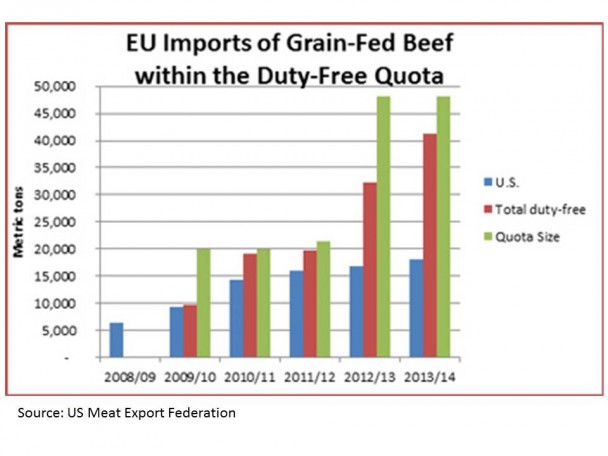

- Phase II (August 2012-August 2013): (a) expansion of the new HQB quota to 45,000 tonnes and (b) agreement by the US to suspend all additional tariffs on EU imports arising from the WTO dispute. The EU quota is administered on a most-favoured nation basis. Over time, additional countries have gained access to this quota which is now shared by six countries: Argentina (added in 2014), Australia (2010), Canada (2010), New Zealand (2011), the United States (2009), and Uruguay (2011).

- Phase III foresees that (a) the EU maintains the HQB quota at 45,000 tonnes, and (b) the US removes its trade sanctions, leading to a long-term resolution of the dispute. Phase III will begin with the official notification to the WTO Dispute Settlement Body of the withdrawal of the case. Parties have not yet reached agreement to enter this phase.

As part of Phase 2, in June 2012, the EU issued regulations increasing the HQB quota for grain-fed beef and changing the quota management system to a ‘first come, first served’ basis. The HQB quota was raised to 48,200 tonnes. In October 2013, the EU approved a two-year extension of the deal until August 2015.

The quota compares to total EU beef consumption of 7.6 million tonnes in 2014, although there is some evidence that US exports are concentrated disproportionately on high-value cuts. The Irish Farmers Association in its recent TTIP position paper estimates that the high-value cuts element of the EU market might represent just 9% of the total or around 700,000 tonnes. Clearly, the HQB quota absorbs a much larger share if that is taken as the relevant market.

US beef exports to EU

To facilitate trade between the US and EU, the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) began operating the Non-Hormone Treated Cattle (NHTC) Program in 1999. The NHTC program certifies US beef for export to the EU by ensuring cattle are not treated with hormones. All producers—farm, feedlot, and rancher—must be certified by AMS to participate in NHTC. Certification requires producers to document adherence to all programme requirements and participate in an on-site visit by AMS to inspect herds, check documentation, and examine feed sources. Producers pay for initial site visits and subsequent compliance audits.

Currently, just 12 feedlots are on the Official Listing of Approved Sources of Non-Hormone Treated Cattle. All cattle intended to be exported to the EU under the current HBQ quota must transit through these feedlots prior to slaughter. Some of these are among the biggest feedlots in the US. One of the accredited NHTC feedlots, AzTz Cattle Co, is currently the 15th largest in the US with a capacity of 144,000 animals distributed over two yards.

In addition, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) certifies slaughterhouses and packing plants that process beef for export to the EU. Packers may incur costs for plant modifications needed to meet EU requirements, such as constructing separate facilities to prevent comingling of nonhor¬mone and other cattle. FSIS also coordinates residue testing of approved plants in accordance with the EU’s Additional Residue Testing Program. Under the rules of the program, randomly selected slaughter facilities must provide muscle cut and urine samples of certified cattle for residue testing. A private lab approved by the EU tests for growth hormones, beta- agonists (including ractopamine), and steroids.

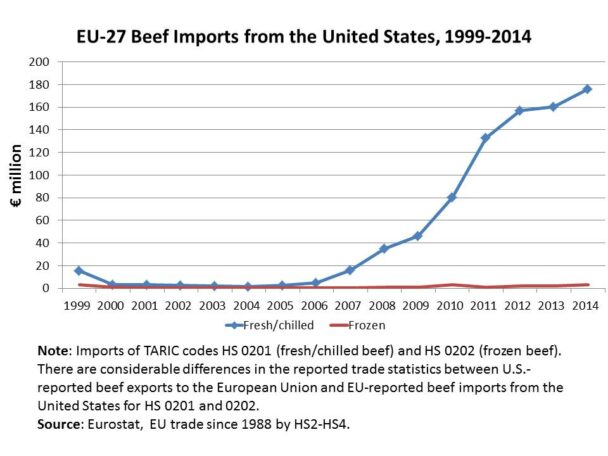

US beef exports to the EU which were worth around $100m per annum virtually ceased following the imposition of the EU ban on the import of hormone-treated beef, but since 2006 have grown along with participation in the NHTC program (see chart below). EU statistics report that EU imports from the US under the duty-free quota reached around 17,800 tonnes during the 2014 calendar year. Note that there are considerable differences between US and EU statistics on US exports, with the US Meat Export Federation, drawing on USDA figures, suggesting US beef exports to the EU have increased from 17,500 tonnes in 2008 to 23,000 tonnes in 2014.

It appears that all US beef now enters under the zero-tariff HQB quota rather than the Hilton beef quota where the tariff rate is 20%. (Update 8 May 2015. Details on the utilisation of the Hilton beef quota for the most recent year confirms that the US made very little use of it in 2012/2014). The overall HQB quota was not filled up to the end of the 2013/14 quota year, but US sources expect that with the admission of Argentina to the quota in 2014, this will change in future and that US beef will be in greater competition with the other suppliers. In the quota year 2013/2014 the US share of the HQB quota fell below 50% for the first time (see chart below).

US sources argue that more US beef suppliers would likely take advantage of the duty-free quota if EU restrictions on the use of antimicrobial washes for the purpose of reducing pathogens were removed (pathogen reduction treatments, or PRTs). In 2009, the EU Commission agreed to seek approval of PRTs for beef. In 2013, the EU approved the use of lactic acid as a PRT on beef carcasses.

Beef imports and TTIP

Exactly what offer the EU might make to the US on beef market access is as yet unknown. The former EU Trade Commissioner Karl de Gucht made clear that the EU will not change its legislation on beef hormones as a result of TTIP. In the free trade agreement with Canada, the EU has offered a tariff rate quota (TRQ) of 50,000 tonnes of non-hormone-treated beef to Canadian exporters (this is made up of an additional quota of 45,838 tonnes on top of the quota of 4,162 tonnes that Canada was given in settlement of the hormone dispute). The EU has not yet made its TTIP market access offer known.

Removing tariffs completely could potentially open the EU market to imports of several millions tonnes, according to the European Parliament report on TTIP and agriculture (p. 60). For this reason, the EU is not expected to offer duty-free access on imports of beef. Instead, it is more likely to make a similar offer of increased TRQ access for non-hormone-treated beef to the US, although the size of this TRQ is as yet unknown. In addition, there could be a reduction in tariffs applying to imports of beef and beef products, even if they are not reduced completely to zero.

In their modelling of the impact of TTIP on the Irish economy, Copenhagen Economics used two assumed scenarios, under which the US is granted an additional quota of 50,000 metric tons of beef in the first scenario and an additional 75,000 metric tons in the second. Under both scenarios it is expected that the US will fully fill the additional quota. Unlike the HBQ quota, this quota would be allocated entirely to the US, implying (under the second scenario) a more than quadrupling of US beef exports to the EU compared to the 2014 level if the quota were fully filled.

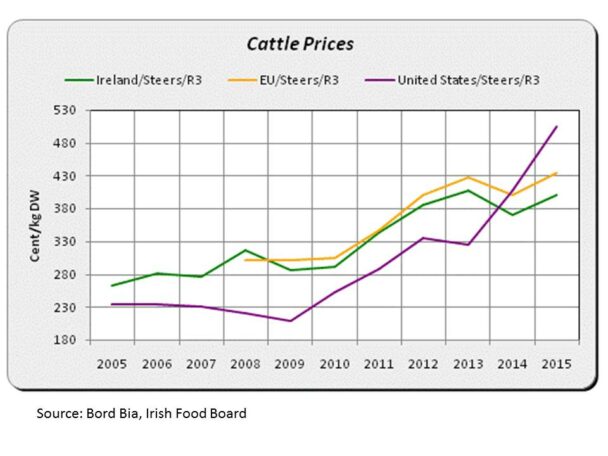

There are two views on the attractiveness of the EU market for US beef exporters. In general, the US is a low-cost beef producer. Production costs are below those in the EU for a variety of reasons, including much larger scale of operation, the ability to use cost-reducing pharmaceutical technologies, cheaper feed and lower land and labour costs. However, some of these advantages disappear when selling to the EU because of the ban on the use of hormones and beta agonists, while also transport costs must be taken into account. Deblitz and Dhuyvetter, from the the agri benchmark Beef and Sheep Network, estimate the additional cost per head of non-hormone-treated beef at around €90 (€30 per 100 kg CW and average CW per animal of 300 kg). They calculate that US costs for non-hormone-treated beef landed in Europe are higher than EU prices (using 2012 as the benchmark year) and conclude that “the total impact of a free trade agreement on beef production in the EU appears rather limited.” (p. 4)

However, this analysis appears to ignore the actual prices received by US exports to Europe which reflect the premium cuts and quality of US beef. The premium for NHTC cattle held steady in the $180 to $200/head range from 2010 through 2013 (€160 to €180/head at current exchange rates). Indeed, the relatively short supply of US cattle at present, and specifically NHTC cattle, due to a prolonged drought has resulted in record-high NHTC premiums in the high $200s – with some reports as high as $300 (€250-€267 at current exchange rates).

The relative attractiveness of the EU market at any point in time will depend on relative US/EU prices and exchange rates. As a result of the recent drought as well as the strong dollar, US beef prices are currently, and exceptionally, above EU prices (see chart below).

Moreover, a recent USDA report on US meat exports to the EU pointed out that a larger TRQ would enable US producers to lower production costs for nonhormone beef by capturing greater economies of scale. As earlier described, the NHTC program imposes significant fixed costs: producers must set up separate production lines and comply with inspection and certification requirements. These costs are likely to require significant scale of production for producers to recoup their investments. Because the EU TRQs cap the amount of beef that can be sold with an NHTC premium, entrance into the NHTC program has been slow and gradual. Expansion of the quota may encourage further participation that could lower operational costs through improvements in economies of scale, further increasing the attractiveness of the EU market.

Historically, US exporters have responded to increasing TRQ allocations. Participation in NHTC has risen along with growth in exports to the EU since the MoU was concluded between the US and EU in 2009. Thus, the conclusion in the European Parliament report on TTIP and agriculture that the elasticity of US supply to further development of the EU outlet is likely to be very large seems to be the more plausible one.

Effects of increased US exports on EU beef production

In assessing the likely impact of increased US beef exports to Europe, two points need to be kept in mind. First, as the European Parliament report noted, a characteristic of the EU beef market is that two thirds of EU beef consumption comes from dairy herds. The supply of such meat is inelastic. This means that in the case of higher imports, the suckler cow sector (which produces only meat) would bear the adjustment costs.

Second, faced with a TRQ volume constraint limiting access to a higher-priced market, the natural reaction of an exporter is to exploit its limited access quantity by exporting higher-value cuts –this maximises the value of the TRQ access. As noted earlier by the Irish Farmers Association, the EU market segment for high-value beef cuts is likely to be disproportionately affected by additional US exports for this reason.

The most recent attempt at quantification is the Copenhagen Economics study for the Irish government on the impact of TTIP for the Irish economy. Recall that this study calculated impacts for the Irish beef industry based on two scenarios assuming additional TRQ access for US beef of 50,000 and 75,000 tonnes, respectively. The study assumes that the TRQ is binding, so the assumed reduction in tariffs on beef imports resulting from TTIP (assumed to be 50% if beef is treated as a sensitive product) is not relevant to the analysis.

The study assumes an import elasticity (i.e. how much imports respond to price) of -7 (higher than the value of -5 quoted as the value preferred by DG Agriculture) to reflect the argument that the main impact will be felt by the suckler cow herd as well as the greater importance of beef from suckler cows in Ireland compared to the EU on average. Any value for the sensitivity of EU prices to additional imports should be taken with a large grain of salt given the complexity and segmentation of the beef market. The fact is that we just do not know what the value might be. Crucially, in the absence of any information on the likely composition of US beef exports between different types of cuts, no changes in the composition of the beef sector as a result of TTIP are taken into account in the Copenhagen Economics study.

The report concludes that output value in the Irish beef processing sector would fall by between 1.7% and 3.2% depending on the scenario. In Scenario 1 (increased US TRQ of 50,000t), the volume of Irish beef produced would actually increase, and the drop in the value of output is due to a (very) small price reduction of 0.1%. In Scenario 2 (increased TRQ of 75,000t), the drop in the value of output is made up of a small drop in output volume of 0.8% combined with a reduction in price of 0.1%. In both scenarios, account is taken of a possible increase in Irish beef exports to the US as a result of reduced trade barriers on the US market.

The results of this study are specific to Ireland but are useful in indicating the order of magnitude of likely effects for the EU as a whole. To repeat, if US beef exports to the EU market are predominantly high-value cuts, the results presented in this study may underestimate the import competition that EU beef producers might face, and could thus underestimate the contraction in output, depending on the extent to which increases in exports of high-value cuts to the US would compensate.

Increased EU beef exports to the US

The European Parliament report concluded that the EU would be unlikely to ship large quantities of beef to the US, a particularly low-cost producer. However, some member states see opportunities. The US market has been closed to EU beef since 1998, following the BSE outbreak in Europe. The US only lifted this ban in March 2014, but the resumption of exports was still dependent on approval of slaughtering facilities by the US Department of Agriculture.

In March 2015 Ireland become the first EU country approved for export of beef to the US. In this first year, the Irish Minister for Agriculture Simon Coveney, has projected exports at 20,000 tonnes with the potential to ‘go way beyond that’ in the future. Many in the Irish industry considered this projection too optimistic, particularly given that American taste favours grain-fed beef rather than grass-fed Irish beef. But already a deal by the Irish beef processor ABF in February brings sales close to the 20,000t target in 2015. Further opportunities are expected once US approval is extended to minced beef.

While the resumption of Irish exports to the US is the consequence of lifting the BSE ban and has nothing directly to do with TTIP, it is worth noting that the anticipated volume of Irish exports to the US would go a long way towards offsetting the impact of an increased TRQ quota for US exports to the EU, at least as far as Ireland is concerned. It may not be the case that comparable opportunities exist for other member states.

Beef in TTIP – how serious is the threat?

Overall, most EU beef production is not competitive on world markets. This is particularly the case for beef from the suckler cow herd. With increased international trade liberalisation, the sector would be expected to contract. Whether this should be a matter for policy intervention or not depends on the weight given to different society concerns. These now encompass environmental, social, health, and climate concerns as well as economic efficiency objectives.

The European Parliament TTIP and agriculture report emphasises the environmental and social objectives. It notes that “[t]he suckler cow sector is perhaps the one sector in agriculture where there are genuine positive externalities. Permanent pasture and extensive grazing have been identified as providing many ecosystem services (for example biodiversity, water management, carbon storage). From a social standpoint, suckler cow production is concentrated in some particular regions and Member States (e.g. Ireland, France), in areas with limited production alternatives, and where the local economy depends a great deal on the livestock sector and the related industry.”

Maintaining the social viability of the European model of agriculture has been identified as a concern in the compromise amendments to COMAGRI’s draft opinion making recommendations to the European Commission on the TTIP negotiations, which are due to be voted on next week April 14, and which also request that Parliament be given sufficient time to evaluate the outcome of the agricultural chapter “focusing in particular on farmers and small family holdings”.

Public health analysts argue that beef consumption in the EU is already above desirable levels and contributes to poor health outcomes for the EU population, even if consumption has fallen significantly in recent years. Easier access for US beef would, ceteris paribus, lower relative beef prices and encourage additional beef consumption. Whether relative beef prices would change in reality as a consequence of a TTIP agreement would depend also on the improvements in market access granted for US poultry and pigmeat exports. Meat consumption as a whole would be expected to increase, although trade policy is hardly an appropriate policy instrument to address health concerns arising from an inappropriate pattern of food consumption.

Another public health angle is the possibility that the EU could remove its ban on hormone use in beef production in the light of updated scientific evidence. The restatement of the EU ban on hormone use in 1996 occurred at the same time as the confirmation of a link between BSE and the human disease variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), “followed by a media outbreak of apocalyptic scenarios sketching a man-made disaster of then unpredictable proportions” (quoting from an EFSA editorial on the European response to the BSE crisis). The EU authorities were desperate to prevent any further loss of confidence in the consumption of beef. Approval of hormone use was unimaginable regardless of the state of scientific opinion.

The situation on the beef market today is very different even if public opinion remains resolutely opposed to hormone use. Were the EU to even partially lift the ban on hormone-treated beef, the relevant constraint on US beef exports would no longer be the TRQ limit but the size of the out-of-quota tariff. Latin American exporters have shown they are able to export beef to Europe even paying the full out-of-quota Most Favoured Nation (MFN) duty (depending on the exchange rate). It would be realistic to assume that US exporters would also be competitive if the tariff on US exports were lowered as part of a TTIP agreement.

Beef production also contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions which the EU has pledged to reduce. Reduced beef production in the EU could thus help the EU to meet its more stringent climate targets to 2030. One argument against unilateral EU action to reduce beef production is that this would simply outsource production to other countries where emissions per unit of production would be even higher – Brazil is usually seen as the alternative source of production in this context.

Under a TTIP agreement, however, EU production would be displaced by US production. There are very different estimates of CO2-equivalent emissions per kg of meat in both regions, depending on production system considered and methodology employed. One recent FAO study put US emissions per kg of meat only slightly ahead of emissions in Western Europe, and much less than emissions from beef production in Latin America (see Figure 12 in that report). Thus concerns that global carbon emissions might increase as a result of TTIP would appear to be largely without foundation.

Finally, changes in EU beef production would be expected to lead to significant economic efficiency gains. EU direct payments typically make up most, if not all, of beef producers’ incomes. Thus, the resources employed in EU beef production are hardly remunerated at all at market prices. Applying the land, labour and other inputs currently used to produce beef in Europe to more remunerative activities would likely yield a significant gain in economic welfare.

These different objectives imply different answers to the question whether beef production should be supported in Europe and to what extent it should be treated as a sensitive product in the TTIP negotiations. The market access offer by the EU will reflect the perceived political balance between these different objectives.

This post was written by Alan Matthews.

Picture credit: Johnny Muck

Dear Alan,… very interesting !

It is a perfect case study for my students (and for me).

Do you have a pdf version of this post ?

Best,

Alessandro

@Alessandro

Thanks for the comment. You can download a pdf of the post here.

Dear Alan,

As always, a very thorough analysis.

There is one aspect of CETA and TTIP that is not addressed in your paper. I don’t know how relevant it is from an economic analysis point of view but it is very relevant from a trade point of view.

Currently what you call the hormone-free TRQ, negotiated by Canada and the US, is open on an MFN basis to all suppliers. The big beneficiaries of this are Australia and Uruguay. The deal already included in CETA, and the likely deal in TTIP, is that Canada will withdraw its demand for compensation under the Hormones dispute (currently 3,200 tonnes) in return for direct access of 50,000 tonnes. Unlike the 3,200 compensation volumes (which are MFN), the 50,000 is exclusive to Canada as it is based on a Free Trade Agreement. This cuts out Australia and Uruguay. It is likely that the same solution would be found for TTIP. Thus the current mfn TRQ is replaced by two country specific quotas.

I don’t see that this affects too much your competitiveness analysis for the US and Ireland but does it have other impacts?

Bernard

@Bernard

Many thanks for this comment, which highlights two additional wrinkles I had not spotted. One is that quota quantities can sometimes be quoted in product weight and at other times in carcase weight equivalent (cwe). The more important point is that the CETA deal involves not just the addition of a Canada-only quota of 45,838t beef on top of the MFN HQB or ‘hormone’ quota’ of 4,162t (this figure in cwe corresponds to your figure of 3,200t in product weight), but rather involves a total Canada-only quota of 50,000t which would replace the hormone quota.

This obviously makes the resulting quota slightly more valuable to Canada because it eliminates the competition from other MFN suppliers for that element which was previously the HQB quota.

Assuming the same logic applied to any additional quota offered to the US, it raises the interesting question of what would then happen to the HQB quota of 45,000t if the concessions to the original two complaining countries are now transferred to tariff rate quotas in bilateral free trade agreements. Would the EU be required to maintain the HQB quota for the benefit of the other suppliers (Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and Uruguay) which currently share in that quota even though it was no longer needed to compensate the two countries which originally won the hormone case? Or would the EU be able to cancel this HQB quota, which would help to offset the economic impact on the EU beef market of extending a larger quota to the US under TTIP?

On a separate point, I could not find any direct reference in the CETA text to the point you raise that Canada, in return for the additional quota, has agreed to withdraw its hormone complaint against the EU. As noted in the post with respect to the EU-US Memorandum of Understanding, the parties have not yet decided to move to Phase 3 where the US actually agrees to withdraw the case. Is it indeed the case that Canada has agreed to do this in the context of CETA?