Every two years the WTO secretariat undertakes a review of the EU’s trade policy including agricultural policy measures which affect trade. The agricultural section of the review builds on the EU’s notifications to the WTO under various agreements, notably the Agreement on Agriculture (particularly the notifications on domestic support, export subsidies and tariff rate quota utilisation) and the notification under the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures. The latest EU trade policy review for 2013 was released last week following discussion in the WTO Trade Policy Review Committee.

The Trade Policy Review provides succinct summaries of the relevant EU farm legislation and policy instruments, even if some of its data (for example, on levels of domestic support) are a little outdated because of the time required to submit the relevant notifications.

The report updates information on levels of agricultural tariff protection provided to EU farmers to 2013. Calculating average levels of protection is an exercise fraught with difficulties for a number of reasons, including the fact that for many agricultural products the EU makes use of specific duties (that is, fixed as an absolute amount) as well as ad valorem tariffs (that is, fixed in percentage terms).

In order to capture the overall level of protection, specific duties must be converted to their ad valorem equivalents so that the total ad valorem protection can be computed (for a discussion of these and other difficulties in calculating tariff averages, see my previous post Will the right tariff average stand up?)

The WTO secretariat has computed these ad valorem tariff equivalents by comparing the specific duties to the average unit value of imports within each tariff category. This is a common approach but prone to bias, and a footnote in the report records the Commission’s reservations with the Secretariat’s calculations. However, the resulting numbers do allow a more comprehensive picture of EU agricultural protection than ignoring the existence of these specific duties.

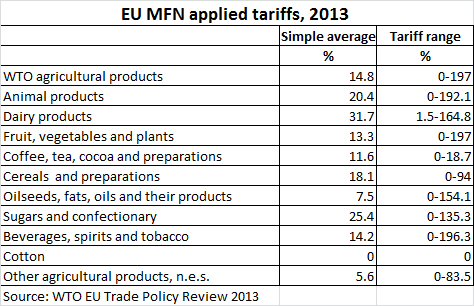

Overall, MFN applied tariffs (that is, the tariffs applied to imports of agricultural commodities (WTO definition) which are not eligible for a preferential tariff rate) fell from 17.8 percent in 2008 to 15.2 percent in 2011 and to 14.8 percent in 2013. Mostly this was due to the effect of increasing world prices reducing the ad valorem equivalent of the specific tariffs. Interestingly, MFN applied rates on non-agricultural products rose slightly over this period (from 4.0 percent to 4.1 percent to 4.4 percent, respectively).

Under the WTO definition, dairy is subject to the highest average tariff rate, followed by sugars and confectionary, live animals and their products, and cereals and preparations (see table below). But very high tariff equivalents apply to specific commodities, for example, prepared or preserved mushrooms (197% and 170%), citrus juice including orange juice and grape juice (196.3% and 165.3%), certain meats and edible meat offal (192.1% and 120.1%), goat meat (166.7%), whey (164.8%), olive oil (154.1% and 120.6%), and isoglucose (135.3%).

The report points out that, by and large, EU farm producer prices are now very close to world market prices, which suggests that these very high tariffs are largely redundant in providing protection to EU producers. However, they still prevent third countries from competing on the EU market in these products, and thus are trade-restricting.

Reducing these tariffs is part of the agenda of the stalled Doha Round of trade negotiations. WTO member countries have another chance to keep this Round alive at the next ministerial council meeting in Bali in December. However, a summary of the state of play at the Trade Negotiations Committee this month (reported in Bridges) does not give grounds for optimism.

Europe's common agricultural policy is broken – let's fix it!