Ireland faces a huge challenge in reducing its greenhouse gas emissions in the coming years. Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Enda Kenny got into hot water last week for apparently saying one thing in his official speech to the Paris COP21 climate conference and another thing in unscripted remarks to journalists afterwards. Much of the subsequent controversy during the week revolved around the Irish government’s attitude to agricultural emissions and whether it was seeking special favours for the Irish agricultural sector in the current negotiations on setting national emissions targets for the period to 2030 in the framework of the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Package. I look at the background to this controversy in this post.

In his speech to the COP21 conference, Mr Kenny pointed out that Ireland’s national long-term vision is presented in climate legislation. This sets out its intention “to substantially cut CO2 emissions by 2050, while developing an approach towards carbon neutrality in the land sector that does not compromise our capacity for food production”. He called for a legally binding agreement on climate change to underpin actions on the goals already agreed and noted that Ireland was committed, with its EU partners, to a collective target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40% by 2030.

Speaking to reporters later, the Taoiseach instead emphasised the difficulties Ireland was facing in meeting its 2020 EU targets. Harry McGee and Lara Marlowe reported in the Irish Times:

The Taoiseach blamed Ireland’s difficulties in meeting targets in agriculture on a “lost decade” which he said was created by recession caused by the previous government. That had resulted in few resources being available to invest in climate change research and infrastructure.

He also said the targets set by the EU Commission for 2020, which called for a 20 per cent reduction of emissions compared with 2005 levels, were “unrealistic” and “unreachable”.

Mr Kenny denied the State was seeking “wiggle room” on the vital sector of agriculture. Rather, he said that when the EU Commission set the 2020 target it had overestimated what agriculture could achieve in terms of curbing emissions.

“We do not want to see a situation where we are limited in what we can produce with the abolition of quotas, to find that food produced in countries with inferior standards and higher emission levels.”

Paul Melia reported in the Irish Independent:

Taoiseach Enda Kenny said financial challenges will prevent Ireland from making deep cuts in emissions from our agriculture sector to help prevent dangerous climate change.

He warned that not until after 2020, and when the economy recovers, would the State be in a position to meet “aggressive targets”.

And he added that “hard bargaining” would take place over the coming weeks to achieve goals which were “fair and reasonable”. Mr Kenny said that existing European Commission targets to reduce emissions from agriculture by 2020 were “unrealistic”.

He said the commission “overestimated” the contribution that the agri-food sector could make, and that as Ireland produced food more sustainably than other countries, it should be treated as a special case.

“We have lost a decade of investment in our country because of what happened. That cannot be recovered, and until we have an economic engine to allow us change structures, and continue to invest in research and innovation for more sustainable ways of doing agriculture, that presents us with a challenge,” the Taoiseach said.

“We don’t want to see a situation where we are limited in what we can produce to find that food is being produced in other countries with inferior standards and higher emissions levels.”

Finally, Ann Cahill reported in the Irish Examiner:

Mr Kenny focused in on agriculture, but with a very different problem from that of poorer countries. While this conference is expected to agree to cut greenhouse gasses, the EU has said it will cut them by 40% by 2030 and the individual national cuts will be decided at the EU level.

Ireland and three other countries were set the highest targets for 2020 of cutting by 20%, something Mr Kenny said was an over estimate of what could actually be delivered given a third of the country’s emissions come from agriculture, mainly the national herd.However, because of the unrealistic target and the economic crisis Ireland is not in a position to reach the goal and if another target is to be added to that for 2030, that will create a real problem, he said.

“I think we will strive to achieve what we can achieve between now and 2020 and the starting point for 2020 should be what we have achieved,” said Mr Kenny.

Mr Kenny’s characterisation of the 2020 target given to Ireland as “unrealistic” and his highlighting of the difficulties in reducing agricultural emissions gave rise to a set of damaging headlines. The Irish Times article had the headline ‘COP21: Kenny criticises ‘unrealistic’ climate targets’ while the Irish Independent piece ran under the headline ‘Climate change is not our priority – Taoiseach’. Friends of the Earth in a press release rejected the Taoiseach’s argument that the recession had made achieving Ireland’s 2020 target more difficult because it reduced the resources for investing in climate mitigation, pointing out that the recession actually made meeting the 2020 targets easier because of lower growth in the intervening ýears.

By the end of the week, the Irish Independent headline had become the story. Three NGOs – Trócaire, Uplift and Friends of the Earth – organised an online petition addressed to the Taoiseach saying that ‘Your comments that ‘climate change is not a priority’ for Ireland at COP21 are offensive and irresponsible.’ Note that none of the press reports quote the Taoiseach as actually saying this.

According to an Irish Times editorial on 5 December 2015:

The problem is his real agenda is to seek an exemption for Irish agriculture in the context of EU targets to cut emissions by 40 per cent by 2030. If that is the case we must make meaningful commitments on other fronts such on eliminating peat and coal-burning power plants and on fossil fuel extraction including fracking – for starters. As Friends of the Earth noted, Mr Kenny “had one story for the world leaders gathered here in Paris and a completely different story for Paddy back home”. Such double-speak is utterly indefensible.

See also this lengthy analysis by Ann Cahill in the Irish Examiner on 2 Dec 2015.

The 2020 target

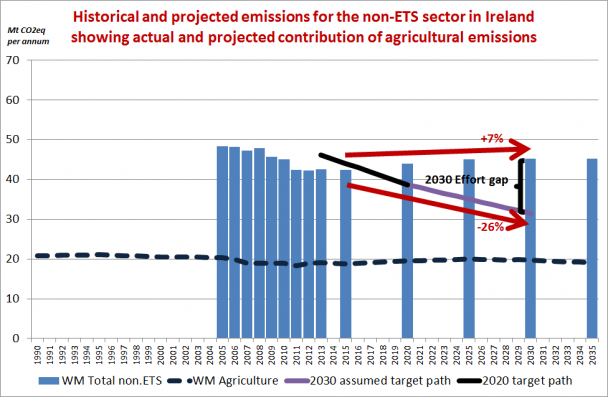

The context for this controversy is recent and projected trends in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Ireland as documented by the Irish Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in its annual update of emission projections. Based on the data in the latest (2015) edition of these projections, I have prepared the following graphic to show the unsustainable path that Ireland is on. (Note that except for the period 2005-2013 the EPA only gives figures at five-yearly intervals in this report. I have interpolated the values for the missing years for the agricultural emissions trend line by assuming linear changes between the five-year data points).

Ireland has a 2020 target to achieve a 20% reduction of non-Emission Trading Scheme (non-ETS) sector emissions (i.e. agriculture, transport, the built environment, waste and non-energy intensive industry) on 2005 levels with annual binding limits set for each year over the period 2013-2020. The black line in the figure shows these annual limits. The figure shows projected non-ETS sector emissions with the measures currently in place. This is called the ‘with measures’ (WM) scenario based on measures and policies in place by the end of 2013 to distinguish it from a more ambitious ‘with additional measures’ (WAM) scenario in which the government’s targets for 2020, for example, for the penetration of renewables or energy efficiency, are reached. As it is not certain that the government’s targets will be achieved without additional measures, the figures from the WM scenario are presented here.

Emissions are projected to be more than 13% over Ireland’s allotted ceiling in 2020. In other words, actual emissions are projected to be only 9% below 2005 levels by 2020, compared to the target of 20% below 2005 levels by 2020.

Agriculture and transport dominate non-ETS sector emissions accounting for approximately 75% of the total in 2020. Emission trends in these sectors are the key determinants in terms of meeting targets.

Agriculture emissions are projected to increase 2% by 2020 relative to 2013 which is the base year for the projections. This reflects the impact of the removal of the milk quota regime in 2015 and the government’s policy to encourage agricultural growth set out in its policy document Food Harvest 2020. Relative to 2005, agriculture emissions are projected to decrease by 4% by 2020 relative to 2005 and by 9% relative to 1990.

Transport emissions are projected to grow even more strongly over the period to 2020 with a 19% increase over 2013 levels in the WM scenario. Relative to 2005, transport emissions are projected to remain the same by 2020 in this scenario.

Targets to 2030

The EPA projections paint a sombre picture of Ireland’s emission trends to 2030 and 2035 in the absence of additional measures. The EPA estimates that by 2035 total non-ETS emissions will be just 6% below 2005 levels in the WM scenario. The estimates of greenhouse gas emissions to 2035 assume a continuation of the effect of policies and measures that are in place in 2020. The EPA recognises that this is a conservative outlook, but the figures are published to illustrate how emissions might look into the longer-term in the absence of any additional policies and measures.

We concentrate on the 2030 estimate because that is the target date for the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Package. Total emissions are expected to increase by 7% by 2030 compared to the estimated level in 2015 in the absence of additional measures.

Ireland’s 2030 target is not yet specified (I discuss this further later in this post). For the purposes of the graph, I have illustrated a scenario in which Ireland is given a target to reduce emissions by 35% compared to 2005 (this is shown by the purple straight line in the graph). This would imply that we should cut emissions by 26% relative to the current year 2015. As we see, the EPA projections show Ireland moving in the opposite direction, with emissions increasing by 7%. There is thus a potential ‘effort gap’ of around 30% by 2030. In other words, Ireland would have to find additional measures to reduce total non-ETS emissions by almost one-third over the next 15 years. Even with the strongest commitment to climate change mitigation, such an effort is a big ask.

Where will this growth in emissions come from? Transport sector emissions are projected to increase by a further 20% in the absence of additional measures over the period 2020-2035. This is driven by an increase in the national car fleet, underpinned by a projected increase in population to 5.3 million by 2035 and a sustained 3% annual average growth in personal consumption over the period.

In the case of agriculture, the EPA projects that emissions will peak in 2025 and decline thereafter to return to 2013 levels by 2035. Underlying these projections is a significant increase in dairy cow numbers, a contraction of around one-quarter in the total beef herd compared to 2013 levels and roughly constant nitrogen fertiliser use.

The impact of forest sinks is not included in this compliance assessment. This is in line with EU accounting rules which do not allow the use of forest sinks to meet EU 2020 targets. However, the EU is committed to integrating the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) sector into its climate change mitigation framework in the period after 2020. In Ireland’s case, the LULUCF sector acts as a net sink, so it would help to bridge some of the foreseen effort gap during the decade to 2030. However, the precise accounting rules and how countries will be allowed to calculate and use LULUCF net emissions has not yet been decided, so we do not yet know how important a contribution this is likely to make in helping to reach the annual targets in the 2020-2030 decade.

Not meeting any targets agreed at EU level for the individual years during 2020-2030 has the potential to cost the country between €50-€500 million annually, depending on the the precise level of the 2030 target, the extent to which Ireland is successful in closing the effort gap, the price which Ireland might have to pay to acquire carbon credits from other countries or the size of any fines which the Commission might impose if we are unable to do that (Update 7 Dec 2015: This paragraph referred originally to a cost of “up to half a billion euro” and has been slightly rewritten to indicate the great range of uncertainty).

The EPA, in its 2015 GHG projections report, summarises the situation as follows:

It is evident that post-2020, in the absence of further policies and measures above those envisaged in place by 2020, that Ireland will face extremely challenging emission reduction obligations…..

Overall it is evident, based on this analysis, that Ireland is not on track towards decarbonising the economy in the long term in line with the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Bill 2015 and will face steep challenges post-2020 unless further polices and measures are put in place over and above those envisaged between now and 2020.

Setting national targets

We now look at the process of setting reduction targets within the EU. This is a three-stage process. First, an overall target reduction for GHG emissions is set at the EU level, divided into sub-targets for the ETS and non-ETS sectors. Second, the non-ETS target is distributed across member states as national reduction targets for their non-ETS sectors. Third, the cost-efficient mitigation options for the different sectors within the non-ETS sector need to be identified (preferably by private actors in response to a uniform carbon tax across the economy, but supportive government policies will be needed in response to specific identified market failures).

The first stage in this process has already been taken. The European Council has now agreed an EU-wide target to reduce domestic GHG emissions by 40% by 2030 compared to 1990, to be achieved by a 43% reduction in the ETS sector and a 30% reduction in the non-ETS sector relative to 2005 levels. Some have argued that the EU should have been more ambitious in setting its 2030 target. The Commission in its impact assessment defended the 40% target as putting the EU on the Low-Carbon Economy Roadmap’s cost-effective track towards meeting the EU’s 2050 GHG objective to reduce GHG emissions by 80-95% in 2050 compared to 1990.

The second stage of the process is dividing the 30% non-ETS target into national targets. Here the European Council decided that efforts would be based principally on the basis of relative GDP per capita. All Member States will contribute to the overall EU reduction in 2030 with the targets spanning from 0% to -40% compared to 2005. Targets for the member states with a GDP per capita above the EU average will be relatively adjusted to reflect cost-effectiveness in a fair and balanced manner. Furthermore, the multiple objectives of the agriculture and land use sector, with their lower mitigation potential, should be acknowledged, as well as the need to ensure coherence between the EU’s food security and climate change objectives.

Recall that the European Council’s conclusions were that member state targets should range between reductions of 0% to -40% by 2030 compared to 2005. The reactions of the environmental and development NGOs might be taken to imply that Ireland should be a climate leader and accept a reduction commitment of -40%. However, a greater reduction commitment for Ireland simply means that all other member states are allocated a smaller reduction; the overall EU non-ETS reduction target stays the same, regardless of the target that Ireland is given. In this context, it is reasonable to ask, what would be a fair and reasonable target for Ireland to have?

As with any policy, the appropriate target has to balance efficiency and equity considerations. Efficiency is an important value in climate policy; we want to achieve the required reduction in EU emissions at the lowest possible cost. This would imply that the cost of abating the marginal unit of carbon required to meet each country’s national non-ETS target should be the same across all countries. If the marginal cost of abatement is higher in, say, Ireland than in Latvia, then the EU could achieve its overall target at lower cost by redistributing the targets.

However, equity considerations may suggest a different distribution of targets than efficiency criteria. Even if for all member states the marginal cost of abatement is the same, the relative burden of measures to achieve these reductions is clearly a greater imposition on poorer countries than on richer ones. Thus the equity criterion points to distributing targets more in line with ‘ability to pay’ the cost of making the necessary reductions.

It is possible to reconcile the efficiency and equity criteria by introducing the flexibility to transfer emission rights between EU countries. For example, if Ireland’s target implies that the domestic measures necessary to reach its target are costing double what it might cost in Latvia to achieve a similar reduction in emissions, it makes sense for Ireland to purchase the necessary emission rights from Latvia. The European Council conclusions promise to enhance significantly the availability and use of existing flexibility instruments within the non-ETS sectors “in order to ensure cost-effectiveness of the collective EU effort and convergence of emissions per capita by 2030”.

It might seem to be a terrible waste of resources to send money out of the country to purchase emission rights rather than to use the money to pursue the low-carbon transition at home. But under the conditions specified we would actually cause greater damage to the economy and reduce our incomes by a greater amount by trying to abate those emissions more expensively in Ireland than paying the Latvians to abate them more cheaply in their economy. Of course, in making these comparisons, we need to factor in the dynamic benefits from investing in the transition to a low-carbon economy rather than rely on a static cost-benefit analysis.

The European Council has decided that the primary criterion in allocating national targets will be ability to pay. It proposes to allocate efforts based principally on the basis of relative GDP per capita. But efficiency criteria are not irrelevant.

If two countries A and B have the same GDP per capita and are thus allocated the same reduction target, but if in one country A the marginal cost of abatement is double the marginal cost in the other country B, then country A is clearly penalized and disadvantaged. It would be reasonable to redistribute the targets between two countries at the same level of GDP per capita so as to equalize the marginal cost of abatement, even if targets for countries with different levels of GDP per capita were set so that the marginal costs of abatement were higher in the richer countries (thus encouraging a flow of finance from richer to poorer member states).

To summarize, given that there are conflicting objectives of efficiency and equity, there is no surprise that countries will haggle over their national targets and it is not necessarily unethical to do so.

In the above example, Ireland is a possible candidate to be considered as country A. Ireland has the highest share of its non-ETS emissions coming from agriculture. The European Council conclusions recognise that biogenic agricultural emissions can be more expensive to reduce than emissions in the energy sector where alternative technologies exist and are becoming increasingly competitive.

The argument about carbon leakage is also a real one. Assuming no change in consumption patterns in Ireland and Europe, reducing agricultural production in Europe simply displaces that production to other countries which may be less carbon-efficient at producing food. Thus, global emissions would increase rather than decrease, which is not the purpose of the policy.

This highlights the importance of addressing the composition of European diets to reduce consumption of animal protein and to reduce unnecessary food losses, which are desirable on both environmental and public health grounds. At the same time, animal protein including milk products are a highly desirable part of global diets and many people do not consume enough. Livestock are also the only way to make use of much of the world’s pasture land and rangelands which otherwise would not make a contribution to the world’s food supply.

Seeking appropriate recognition for the role of the LULUCF sector as a sink also makes sense provided that the rules genuinely reward additional effort and that the overall integrity of the carbon abatement effort is maintained.

Putting these arguments on the table should not be regarded as special pleading. The debate in Brussels now is about burden-sharing, not about the level of climate ambition which was settled last year. When the dust has settled, the EU will still reduce its non-ETS emissions by 30% compared to 2005 levels, regardless of the target that Ireland accepts.

In its 2020 targets, Ireland was assigned the maximum reduction commitment among member states. In the graphic above, I have assumed a target reduction of -35% which is somewhat less than the maximum -40% in the range set by the European Council. If the eventual reduction target assigned to Ireland is less than -35%, then the effort gap by 2030 shown in that figure is also reduced.

But on any plausible expected target, it is clear Ireland must do much more than is currently planned to address its unsustainable emissions trend.

Meeting Ireland’s emissions targets

This now moves the focus to the third stage of target-setting, namely, the contribution that individual sectors can make to achieving Ireland’s emissions reduction target by 2030, whatever that may be. Individual sectors will not be given specific targets under Ireland’s mitigation framework so the word ‘targets’ is used loosely to denote the expected contribution to be made by each sector. In this context, attention has focused on the projected expansion in agricultural output, supported by government policies set out in Food Harvest 2020 and Food Wise 2025, and the extent to which this is consistent with the overall requirement to reduce emissions.

Farmers are now giving greater attention to increasing the carbon efficiency of their production, and tools such as Teagasc’s Carbon Navigator are helping farmers to identify where improvements can be made. In general, improving carbon efficiency also contributes to improved farm income and hence makes good business sense.

Yet despite the projected improvements in carbon efficiency, the EPA projections show agricultural emissions flat-lining over the years to 2030 when we need to see them on a downward trend. Netting out the likely sink effect of LULUCF actions such as increased afforestation would improve the trend somewhat, but the question is, can we do more?

A major source of agricultural emissions is the beef suckler herd. Ireland has the fourth largest beef cow herd in the EU. The EPA projections assume that some of the increase in dairy cow numbers will be offset by a contraction in beef cow numbers, but a sizeable suckler herd will remain. A Beef Data and Genomics Programme has been introduced, funded by the CAP Rural Development Programme (RDP) over the period 2015-2020 to the tune of €295 million. The aim is to lower the intensity of GHG emissions by improving the quality and efficiency of the national beef herd. However, there is no target given in the RDP for what reduction in emissions might be expected from this measure, so it is impossible to decide if this is a cost-effective way of reducing emissions or not.

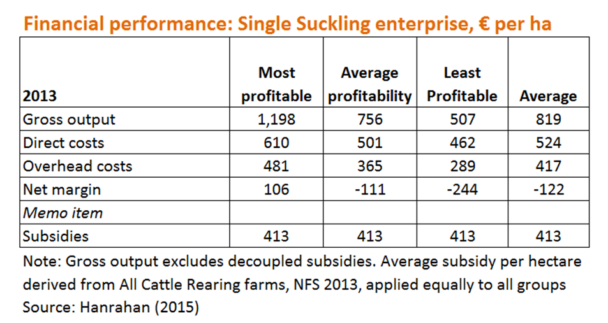

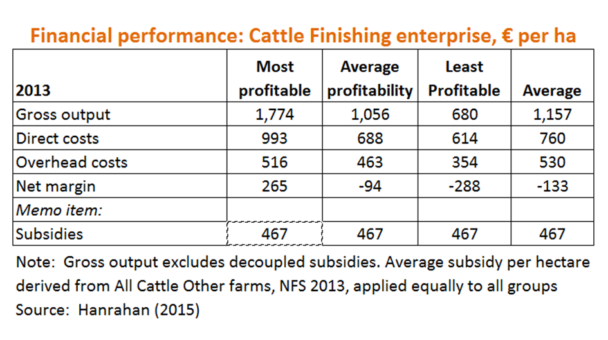

The difficulty is that much beef production in Ireland does not cover its costs and is subsidized out of farmers’ direct payments. Financial analysis in the Teagasc National Farm Survey for the two main beef production systems show that the least profitable third of farms in both systems barely cover their direct costs from the money they make selling their beef, and beef production on these farms is a significant loss-maker when overhead costs are factored in. If, in addition, the Irish taxpayer ends up paying considerable sums to other countries to pay for the carbon emissions on these farms, the absurdity of the situation becomes clear.

The meat industry has argued that “It would be foolhardy in the extreme to curb the production of beef in a country where we produce in an extensive grass-based system that is far more efficient and sustainable than elsewhere in the world.”

But this argument does not make sense. We should encourage the production of beef and dairy products where it is profitable to do so once the full costs of production, including the cost of carbon emissions, are factored in. There are efficient and profitable dairy and beef producers in the country who do meet this criterion. But there is no case for the Irish taxpayer to further subsidize the production of beef in Ireland when beef production does not even cover its costs on many farms. There is more to efficiency than just carbon efficiency.

The argument also does not make sense from the individual farmer’s point of view when there are alternative land uses which would return a higher income. On many farms, converting some or all of the land to bioenergy crops or forestry would yield a higher return to the farmer. Changing land use in this way would have a double dividend because it would both reduce emissions from livestock and increase the value of the carbon sink from afforestation (see this previous post and the links there to a more detailed exposition of this argument).

There are of course reasons why this desirable transition is not taking place fast enough. Many of the farmers concerned are older, and it is asking a lot of an older person to change to an enterprise where the main income benefits will be reaped after that person’s death. No one likes to see their industry contract in size. Older farmers have grown up with cattle farming and there is a high social and cultural attachment to the role of cattle in rural Ireland.

But that is no excuse for not taking action. We cannot argue at the EU level that our emissions targets are unrealistic when we fail to exploit the opportunities we have to reduce our emissions in a cost-efficient manner.

The National Policy Position on Climate Change, which was published at the same time as the final Heads of the Climate Action and Low-Carbon Development Bill in April 2014 by the then Minister for the Environment Community and Local Government Phil Hogan, commits, as a fundamental national objective, to achieve transition to a competitive, low-carbon, climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable economy by 2050. This should include developing a land use strategy which makes its full contribution to achieving this goal.

This post was written by Alan Matthews. I am a member of the Climate Change Advisory Council, but the views expressed in this post are my personal views, and should not be taken to represent or prejudge the views of the Climate Council.

Photo credit: © Copyright Steve Daniels and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.