The EU dairy market is now recovering from the severe drop in milk prices in 2009. Perhaps the clearest sign of this recovery is the setting of export refunds on dairy products to zero since mid-November, as world market prices for dairy products have strengthened in recent months.

It is thus an opportune time to evaluate the EU’s response to the crisis, and to see what lessons might be drawn for how the Union can address similar problems in other farm sectors in the future. My view is that there is a lot to be learned from the dairy crisis, and that the outgoing Commissioner deserves credit for the way she handled it.

EU milk prices improving

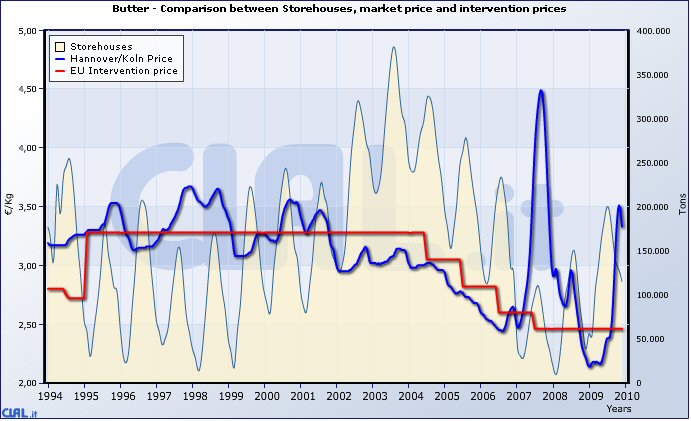

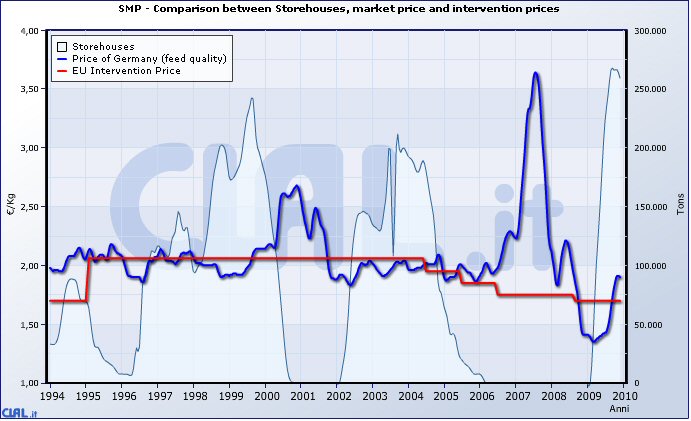

Let us first review the evidence that the milk market is improving. The trends in the EU market prices (proxied by the German price and represented by the blue line) and the EU intervention price (the red line) for butter and skim milk powder (SMP) have been graphed by CLAL.it and are reproduced below.

The German butter price is now back to the level of 2002 before the cuts in intervention prices. The recovery in SMP prices has not been as strong, but even so these are now comfortably above intervention levels. EU dairy farmers also benefit from an additional €5 billion per year in the form of direct payments (3.5c/kg milk) to compensate for the reductions in intervention prices.

Farm prices are responding to the better prices for dairy products, although with some lag. The average EU price for standardised 4.2% fat milk, according to the LTO, has risen to €27.06/100kg in October 2009 from its lowest point of €23.74/100kg in April. It is now back at the levels of Spring 2007, before the big run-up in prices in 2008.

The recent USDA market outlook for dairy products in 2010 foresees continued strong prices into 2010 as economic growth recovers particularly in developing countries. While the large stocks of SMP in particular overhanging the market are seen as a negative factor, it observes that in the US most of these stocks are committed for domestic food programmes and that the EU is unlikely to release its stocks on to the market soon for fear of the political fallout from producers.

The Commission’s response to the dairy crisis

Assuming that prices continue to strengthen throughout 2010, it is useful to review what lessons were learned for crisis management when faced with a substantial fall in the price of a farm commodity. The Union’s responses to the collapse in domestic milk prices in 2009 can be divided into market management measures and income support measures.

Among the market management measures were

In total, the Commission expects to spend up to €600 million on market measures this year.

Among the income support measures were:

Reflections on the Union’s response to the dairy crisis

A first observation to make is that, while the Commission did resort to market management measures such as intervention and export subsidies, much more emphasis on this occasion was put on income support measures.

It was noticeable that the Commissioner firmly set her face against any increase, even temporarily, in intervention prices and against a reduction in quotas, arguing that both would be against the spirit of the Health Check intended to move the CAP in a more market-oriented direction.

Although the future of export refunds after 2013 is uncertain (the EU has committed to their elimination but only in the context of a successful outcome of the Doha Round in which similar disciplines applied to other forms of export support), it is likely that the greater emphasis on direct income support measures in response to crisis is here to stay. While the loud voices calling for stronger support measures as part of a food security policy for Europe would doubtless like to see stronger market management measures, these are effectively beggar-my-neighbour responses unless undertaken as part of a global framework (e.g. a global stocks policy).

A second observation is that the income support measures included both a relaxation of state aid restrictions (allowing Member States to fund payments to producers) and a Community scheme. While the national state aids were permitted only in the context of a measure taken as part of a wider response to the economic crisis, they do flag a possible direction for future responses to agricultural market crises. When the figures come in, it will be interesting to assess how much use the individual Member States make of this opportunity.

A third observation is that the payments will be made to producers only with a lag (the exception is the speeding up of the disbursement of the standard Single Farm Payment). This means that payments will reach farmers after the crisis has passed and when incomes are already recovering. Clearly, payments should reach farmers at the time when they are most needed, and hopefully the decision to allow the Commission to respond to future dairy market crises on its own initiative may facilitate this in future.

A fourth observation is that there is now little headroom in the EU budget up to 2013 to fund unexpected crisis management measures. The outgoing Commissioner has made clear that funding the €300m emergency aid from the 2010 budget has utilised any remaining headroom and, apart from the use of the safety margin, any further call on the agricultural budget would trigger the financial discipline mechanism requiring a cut in direct payments.

Price volatility on agricultural markets is expected to increase in future (though whether this is a reasonable presumption to make deserves further analysis, and the outcome depends on the interaction between production shocks and their distribution where climate change is expected to increase volatility, trade policies and their implications for price transmission from world to national markets, and government behaviour particularly with reference to stocks).

Presumably these lessons will be analysed by the High Level Experts’ Group on Milk which is looking into the medium and long-term future of the dairy sector and which will deliver its final report by the end of June 2010. A very useful input is the report on price volatility in the dairy sector commissioned by the European Dairy Association and written by my Irish colleagues Michael Keane and Declan O’Connor.

The 2009 EU dairy market crisis was handled well by the outgoing Commissioner. There was no back-tracking in the direction of CAP reform, and a number of innovative new instruments to address income volatility in a particular sector are being tested. The lessons learned from this experience will be an important input into the discussions on the shape of the CAP post-2013.

Update 5 January 2010: When writing this post, I had not seen that the French have made use of the national state aid provision to provide up to €700 million to farmers affected by the crisis. Aid under this new scheme can be granted until 31 December 2010 and will take the form of direct grants, interest rate subsidies, subsidised loans as well as aid towards the payment of social security contributions. See http://europa.eu/rapid/pressReleasesAction.do?reference=IP/09/1866&format=HTML&aged=0&language=EN&guiLanguage=en,