I want to revert to the topic of the capping of direct payments under the CAP, which I last discussed here and here. It is not the most important issue in the Commission’s legislative proposals for the CAP after 2020. But the issue of the fairness of direct payments was raised as an issue in the CAP Communication, and the proposed capping has been defended as a significant step in the better targeting of these payments. There is thus some interest in asking how effective it is likely to be.

The current situation

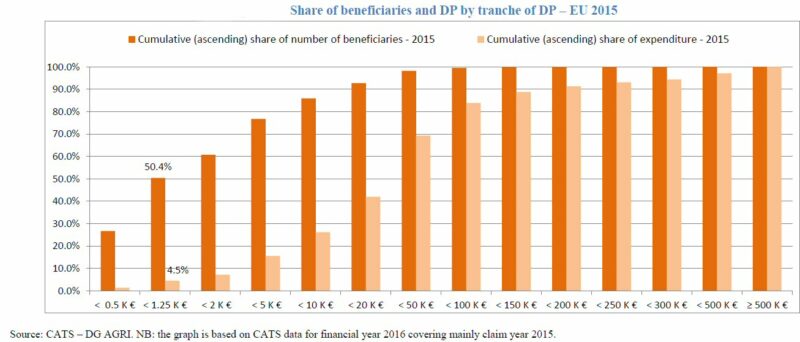

The current situation reflecting the distribution of payments in claim year 2015 is shown in the following graph. The graph shows the cumulative number of beneficiaries and their cumulative share of total direct payments in that year. What emerges clearly is the large number of very small beneficiaries. On average, at EU level, half of the direct payments beneficiaries receive less than €1,250 per year (around €100/month), corresponding to 4.5% of the total direct payments envelope. What is less evident is that just 2% of beneficiaries (121,000 farms) receive 30% of the total direct payments envelope (those receiving more than €50,000 in total).

Although modulation of direct payments was introduced in the 2008 CAP Health Check, capping as such was first introduced in the 2013 CAP reform but on a voluntary basis. In the final regulation, amounts of basic payment (the BPS and SAPS) above €150,000 must be reduced by at least 5%. Member States could increase this percentage up to 100%, thus introducing a de facto cap. Member States could also decide to apply this reduction after having subtracted the salaries paid by the farmer from the amount of basic payment. Also, the Member States that allocate at least 5% of their national envelope to the redistributive payment do not have to reduce payments.

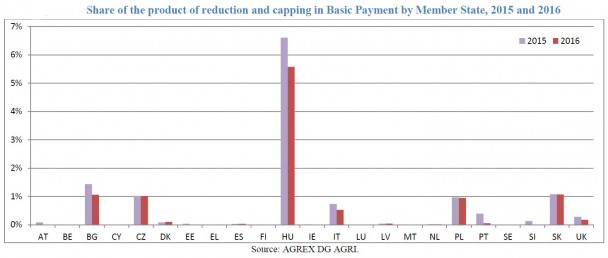

For 2015, according to the Commission, the product of the reduction (including capping) amounted to €98 million, and in 2016, it amounted to €79 million, representing only 0.36% of the basic payment expenditure. Even in Member States implementing the capping, this product has remained generally low except for Hungary, where the product of reduction and capping (set at €176,000) represents 6.6% of the envelope in 2015 and 5.6% in 2016. The difference between the percentage of the reduction and capping between 2015 and 2016 can be explained by an increase in the basic payment (SAPS) envelope in BG, and by a lower value of high-value payment entitlements due to internal convergence in BPS in other Member States.

Impact assessment

To assess the impact of capping the level of DPs to reach a fairer distribution of support, the Commission’s impact assessment simulated two levels of capping per farm, €100,000 and €60,000. In the impact assessment, only the capping of the basic payment and the redistributive payment were simulated. The impact assessment tested different scenarios where Option 1 is a modified baseline. This assumes the continuation of current CAP rules to 2030 but with a linear reduction in the envelope for direct payments by 10% due to the hole in the budget left by Brexit (the actual reduction proposed by the Commission in its MFF proposals is less than 4% in current prices, but with a correspondingly larger cut in Pillar 2 spending).

The other scenarios tested reflect different priorities in targeting direct payments and differ in many dimensions. Both Options 3 have a strong environmental focus, Option 4 gives equal priority to income support and the environment, while Option 5 has a strong focus on redistributing support to smaller farms and the environment. For our purposes, the most important difference between the scenarios is the amount of direct payments allocated to the basic payment including the redistributive payment, as this determines the base for the calculation of the threshold to which the reduction in payments and capping would apply. Option 3 shows a sharp reduction because Member States are assumed to allocate a high share of Pillar 1 payments to the eco-scheme. Option 5 also shows a sharp reduction because a higher share of Pillar 1 payments is allocated to top-ups for extensive livestock farming, ANC areas and organic farming.

The model used for the scenarios (IFM-CAP) is based on most of the farms in the FADN dataset. Even though we might expect the very largest farms not to be well represented in the sample, its estimated proceeds of the reduction and capping in 2030 corresponds reasonably well with the actual proceeds in 2015 and 2016 (an estimated €120 million compared to actual €80-100 million).

The significance of the base for calculating the threshold is shown by the different scenarios shown for the updated baseline Option 1 in the table below. The more extensive is the base, the higher the proceeds of capping. In Option 1, only those Member States that currently apply capping are assumed to continue to do so, and at the thresholds currently applied. Despite the possibility to apply a correction for salaries HU, PL, SK and CZ do not apply it, because it is deemed too complicated.

The outcome of the modelling of the different Options is that, once it is assumed that salaries are fully deducted before the cap applies, there is essentially no impact of capping. Even in Option 5, where the cap is reduced to €60,000, the proceeds from capping are a mere €50 million.

The impact assessment (IA) also gives the number of farms affected by capping and their average income in the different Options. Farm income in the impact assessment is defined as Farm Net Value Added. These figures may appear low, as it is the very largest farms affected by capping that are identified in this table, but make sense if they are interpreted as farm income per AWU rather than per holding.

Differences with the legislative proposal

There are several differences in how capping would be implemented between the modelled scenarios and the legislative proposal. The legislative proposal would set a mandatory limit to payments at €100,000 but this limit could be reduced to €60,000 at a Member State’s discretion. In any case, degressivity would be applied to amounts above €60,000 as follows:

(a) by at least 25% for the tranche between €60,000 and €75,000;

(b) by at least 50% for the tranche between €75,000 and €90,000;

(c) by at least 75% for the tranche between €90,000 and €100,000.

Importantly, capping would apply to all Pillar 1 payments, including coupled payments and eco-scheme payments. This would be a considerably stricter threshold than modelled in the impact assessment. Also, the direct payments budget will not be cut by as much as assumed in the impact assessment. On the other hand, an implicit charge for family labour as well as salaries can be deducted from the payment before the capping is applied. For these reasons, it is not possible to extrapolate directly from the modelling results to the likely impact of the Commission proposals. However, the general conclusion that capping is not likely to release significant amounts of funding for the redistributive payment or other purposes is likely to remain valid as long as salaries and the implicit cost of family labour can be deducted from the payment before the cap is applied (as I argued here).

Criticisms of capping

The argument in favour of allowing the deduction of labour costs is that capping penalises farms providing numerous jobs. Capping and the reduction of payments in the current CAP programming period mainly affects HU, PL and BG. In these countries the capped farms have close to 50 employees on average (Annex 5.5 of the impact assessment shows the figures).

However, criticising capping on grounds that it discriminates against employment does not make sense. If it were the case that the largest farms were discriminated against in this way (and large farms have other advantages such as economies of scale and economies in buying power), the land would not go out of production but would be farmed by smaller units. The evidence suggests than smaller units would be as labour-intensive (in terms of labour units per hectare) than the very large farms or even more so. Thus a cap, other things equal, would as likely lead to higher employment in agriculture as the reverse (this earlier post has a more detailed discussion of this point).

A possible counter-argument is that capping large payments might encourage large farms to adopt more labour-intensive enterprises as part of their product mix in response to the cap. In effect, if they are capped, these farms could increase their labour use at effectively zero cost (their higher wage bill would be offset by an equivalent increase in their direct payment income).

Jan Pokrivcak and his colleagues examined the situation regarding capping for corporate farms in Slovakia. There were 2,275 such farms in 2012, but full data on payments and salaries were only available in the Ministry database for 1,201 of these farms.

On those farms likely to be affected by capping under the Ciolos proposal (41 farms in total), mainly farms growing cereals and oilseeds, the mean number of Agricultural Work Units (AWU) per 100 ha was 0.53 and the median 0.52. On those corporate farms that would not be affected, which had a greater share of animal production, the mean number of AWU per 100 ha was 5.23 and the median number was 2.03.

Thus, if the ability to deduct salaries encouraged some primarily arable large farms to adopt a more labour-intensive animal enterprise, it could lead to higher employment. Other reactions are also possible, such as replacing external services such as for harvesting (as suggested by Sahrbacher and colleagues in this paper). However, given the relatively small number of farms that would be affected, and the even smaller number that might alter their behaviour in this way, the expected employment gains would be rather small.

A second criticism made of capping (and raised by journalists at Commissioner Hogan’s press conference when he announced the legislative proposals) is that the affected farms could avoid it by dividing up their holding. The Commissioner’s response was that there is nothing in law at present in any Member State that prevents a single farmer from owning and operating more than one farm. In claiming the basic payment, all land farmed within a country by the same individual is treated as a single holding. Thus, to reduce the exposure to capping, ownership of part of the holding would have to be transferred.

I do not know whether under CAP rules transferring ownership of part of a corporate farm to a different company with the same shareholder would constitute a sufficient change of ownership for this purpose. The direct payments regulation includes an anti-circumvention clause (Article 60 of Regulation (EU) 1306/2013) which states that “no advantage provided for under the Basic Payment Scheme, the Greening Payment Scheme and other Direct Payment Schemes/Rural Development Programme measures will be granted to farmers where it is established that the conditions required for obtaining such an advantage were created artificially contrary to the objectives of the Regulations governing these Schemes.”

A third criticism of capping is that it discriminates against efficiency and thus reduces the long-term competitiveness of EU agriculture. This argument assumes that larger farms, due to economies of scale, are indeed more efficient that small or medium-sized farms. While the continuing structural concentration of farmland is evidence of the importance of economies of scale, a proper assessment would require a full accounting and inclusion of the environmental costs and benefits of farms of different scales. Capping area-based payments does not rule out possible support, for example, for investment in new technologies, for risk management or for financial instruments, that may be more relevant for these types of farms than for smaller farms.

It is also important to take the structural context into account, as illustrated in a paper by Balmann and Sahrbacker. In Germany, there is a strong spatial segmentation of small and large farms, with the latter concentrated in the former East Germany. In this case, the introduction of capping has almost no effect on farm structural change. This is because large farms whose payments are capped, in the large farm regions, compete for land mainly with other large farms in the same situation, whereas small farms, that are not affected by capping, and that may benefit from a redistributive payment not considered in this post, compete for land with other small farms in the same region that have also received the same benefit. The result of this spatial segmentation is that capping has no impact on the likely survival rates of large farms and would simply be reflected in lower land prices and rents.

Conclusions

Capping provided a contentious element in the 2013 CAP reform discussion. All signs suggest that the Commission’s proposal for mandatory capping, even if made almost irrelevant by the ability to set off labour costs, will be equally contentious in the negotiations on the current legislative proposals for the CAP after 2020.

The Commission’s justification of capping is to improve the fairness of direct payments. Indeed, in the public consultation that preceded the publication of the Commission Communication in 2017, when asked to choose the most relevant five criteria out of ten possible to allocate direct support, distributional issues (either focusing support on small farmers or capping) were mentioned by a quarter of farmers and organisations and by a third of other citizens. When payments are made simply based on control of land, it is clear many people find it difficult to justify large payments to already wealthy individuals or companies.

Implementing a rigorous cap on payments in these circumstances is clearly better than not doing do, but I would question whether it would lead to a ‘fairer’ system. Many small farms have reasonable incomes, for example, if they operate vineyards or horticultural enterprises; others are managed as part-time farms where the farm income may be relatively small compared to the off-farm income of the household. Some large farms do more for the environment depending on the way they are managed. If direct payments were used to remunerate farmers for non-marketed services that would otherwise not be provided, then the size of farm should not be relevant.

From this perspective, the Commission’s proposal that eco-scheme payments in Pillar 1 would count towards the threshold for capping would seem to be perverse. Encouraging these larger farms to engage in more sustainable farming practices is something to be encouraged, not least because of the high share of agricultural land that they control. In addition to removing or limiting the deduction for salaries, this would be a further change I would suggest to the Commission proposal.

This post was written by Alan Matthews

Update 17 Sept 2018: The reference to the income figures for farms affected by capping in the Commission’s impact assessment has been clarified.

Photo credit. Grain field in Slovakia via Pixabay, used under Creative Commons CC02 licence.

There are other arguments against capping. Farmers often have the benefit of capital while farm employees will rarely have access to capital and may not even have security of tenure over their home. Almost by definition they are usually in a remote situation without access to other employment. Worse still farms are invariably overmanned. I have managed or consulted on businesses where all labour on 400ha of combinable cropping is supplied by one man (farmer or manager) with casual at harvest. Many are familiar with large dairy farms with 1 employee per 200 cows. BUT even in the UK employment is in practice three times these levels. The impact of capping is to force through lower labour levels..

Subsidy itself is evil since it changes the risk equation for making land available. It may not be the way economics should work but a high return risk free means that other income is not looked for. Don”t forget most farms are also someones home and garden. When was the last time you looked for a higher return on your house?

Thx for comment, Simon. Not sure that I buy the argument that farm workers benefit from direct payments. Wages paid will be set in local labour markets, or increasingly with farms relying on immigrant workers, on the relationship with wages in the source country. Any change in direct payments will be reflected in the income of the farm owner, but not hired workers. But I do accept that providing more support to smaller farms will tend to slow down structural change by making less land available

Dear Alan,

refering to the dispute on the non-sensitivity of capping I would like to add several aspects.

a) At least in Germany, most large farms are legal entities, that means as soon as their is not a 100% control of one firm over the other, they are two farms. Due to the cooperative structure that is rarely the case. As a consequence they are different receipients of payments. In addition at least under the current German legal framework you are more less free to organize your management units as you like as long as it makes some economic sense. To make it straight, I do not see any plausible limit to determine which degree of dissimilarity between the ownership structure of two entreprises one should require to define them as two companies, and based on what criteria? Invested assests, votes, attribution of profits, …?

Tietz provides a nice overview on the situation (https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/dn059268.pdf). Unfortuantely only in German.

b) Administering the capping with deducting labour costs will be an adminsitrative nightmare for the member states. This would be exagerated if one would like to disentagle all the cross and inter-relation among forms. As labour force in the civil service is also limited, the introduction of capping would massively distract ressources from tasks that could definitely produce greater impact.

c) Thanks for pointing out that the capping also includes the ecoschemes. This inclusion basically thwarts the concept of ecoschemes. The ecoscheme are paid for an environmental service. Environmental service are frequently related to the amount of land ressources available. Consequently, if somebody has more land and does more on this land why shouldn’t he receive more funds? A recent analysis that we going to publish in the comming weeks shows, that for a couple ennvironmental impact indicators large farms perform on average better, especially if compared to classical family farms managing something between 20 and 200 ha. The result are based on data from six german federal states. (Some first results are presented in Nitsch et al., 2018 (DOI:10.17433/6.2018.50153583.258-265) and Röder et al. 2018 (DOI:10.17433/6.2018.50153581.250-257)

Best

Norbert röder

@Norbert, thanks for these very useful insights showing how complex the capping proposals could be given the very different ownership structures of farms across Member States. I look forward to reading your study on comparing the environmental impact of large and small farms, it will be very useful to get some good data on this vexed issue.

A major part of large farms in Lithuania, as in Germany, are legal entities. There was no private property in Former Soviet Union; concerning agriculture — only collective farms proceeded there. After independency they were privatized by their employees. The majority of these persons decided to farm individually. Part – decided not to divorse, but leave joined property and intellectual capital. Thus, large farms were established as deeply integrated co-operatives. Let’s imagine another situation where members of cooperative delegate to it fulfilling of crop declaration and … became subject to capping. In these cases, can one found even traces of coherence and consistency of EU policies – iniciatives strengthening farmer’s posintions in food chain by facilitating cooperation, producer groups, and so on?